What makes us truly and fully human? What tools, techniques and technologies enhance and reinforce our humanity? And given the vast diversity in how humans live and what they want, could there ever be a single answer, or set of answers, to the question “what is humane about technology?” What is humane-tech?

The juxtaposition of the ideas of humanity and humane-ness with technology and innovation raises hard problems and immediate concerns. The problems may have no solutions, and may only invite the construction of provisional, even tentative, and perhaps appropriately, humbling arrangements between humans and their machines.

A chief reason to embrace humility can be found in the inherent limits of language and thought. There is a risk of circularity, or tautological expression, when we turn to the task of making sense of the relation between humans and their tools, between human communities and their complex systems of support.

For instance, consider this paradoxical question: since all tools are made by humans, must not all human-made tools express our humanity? Are tools and technologies inevitably humane because they’ve been made by humans, and thus are extensions of someone’s humanity? If not my humanity then someone else’s? And so, bluntly, am I then also responsible for them, despite my clear-eyed everyday sense that some innovations are humane while others are not?

The boundary between the human-made world and humans themselves is increasingly hard to draw. So should humans be defined by their tool making? The Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga famously asserted something along these lines when he defined humans as a species of players, dedicated to amusing ourselves and others. In this context, Huizinga said the essence of humanity is defined by improvisational activities; hence his decision to categorize humans as homo ludens. Today, given the primacy of digital technology in mediating human experience, might we now call humans homo technologicus? Aren’t we a species fundamentally shaped by personal technologies: past, present, future?

So is the entire project to humanizing technologies — to decide that some are humane and others are not, folly— doomed to failure? And I don’t mean doomed because humans themselves often lack foresight. Stephen Toulmin, the British philosopher, considered foresight essential to the anticipatory reflex required to make sound judgements, in advance, about whether a tool is humane or is not, and should or should not be built and adopted. That’s because once the tool is created and let loose in the world someone will find a humane use for it, or at least claim to do so. So anticipation, foresight and understanding would seem to be essential for any ethical, sustainable approach to technological innovation. Yet at the same time that seems essentially impossible.

There’s also the other nagging suspicion that when we reject a new tool as inhumane we sometimes do so in order to mount a celebration of our unique, and highly questionable, conception of the virtues and manifest destiny of our own species, or even our own selves. For instance, if I subscribe to the view that resistance, rebellion and revolution are the highest forms of human social expression (following Camus, and in contrast with many conservative thinkers), then naturally I will favor innovations that seemingly strengthen capacities for advancing those “three Rs.” (We might think of them as the pillars of visionary engineering.) Yet any such conclusion should raise worries about a tendency to confuse one’s own particular values with a general, or universal, approach to responsible innovation.

Another angle on our shared dilemma is the possibility that we will reject in high-minded fashion a new tool in order to reinforce power relations and imbalances that some agents may cherish but whose victims do not. I think here of the opposition by the poet and essayist Wendell Berry’s to using a computer. Writing in Harper’s magazine in 1988 on “why I am not going to buy a computer,” Berry memorably argued that a computer would tether him to massive, impersonal electricity grids which he sought to resist on humane grounds. “I try to be as little hooked to them as possible,” he insisted. And by the way, who needs a computer anyhow, Berry wrote exultantly, because “my wife types my work on a Royal standard typewriter bought new in 1956.” In the ensuing celebrations and excessive praise over Berry’s brave opposition to digital machines and his fidelity to manual typewriters, no one seems to have ever asked Berry’s wife if she would like a computer. She was the one stuck typing her husband’s writings!

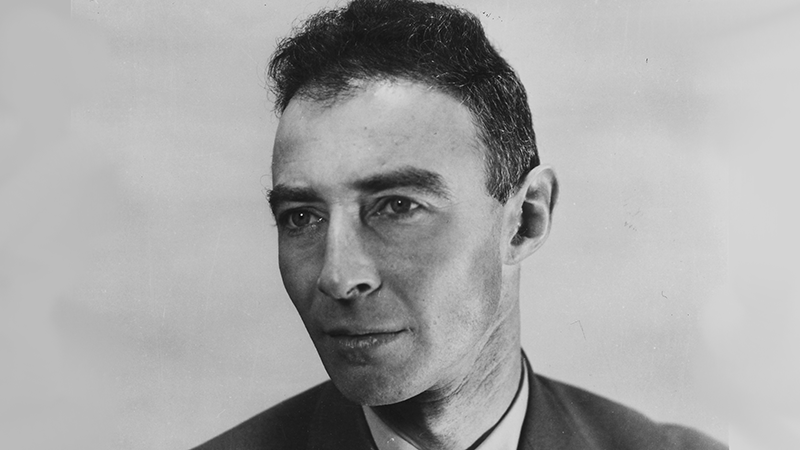

Let me close with a more unsettling possibility. What if, perversely, our own militant sense of humanity explains why our technologies end up dehumanizing us? Remember, the guillotine was an Enlightenment technology that supposedly helped “humanely” rid us of reactionaries. The electric chair (obsessively pursued and partially financed by great inventor Thomas Edison) was presented as a humane way to execute those undeserving of life. And the mythical radiation-free H-bomb was pursued by Edward Teller, which dissuaded President Eisenhower from supporting a ban on H-bomb tests.

What if, to put it crudely, we humans are bad enough that as we more fully realize our humanity, through the power of harnessing techno-science, we succeed in merely making our technologies more doubled-edged? Can there be any doubt that some humans are truly bad and that others, through lack of foresight about the effects of their values and actions, will engender undesirable outcomes?

We know about the persistence of good and evil. But many of us now seem to insist that sometime late in the 20thcentury, humanity passed a tipping point, decisively repudiating the inhumanities of our inherited past. Many seem to believe that we have now entered a new epoch, in which commitment to fairness, justice and equity permeates our emerging technological systems so profoundly that these systems will inevitably reinforce, sustain and propagate our new post-exploitative values.

Before we reflect on whether the above scenario is realistic, let us say together: humility first, before we applaud our good judgement.

G. Pascal Zachary first delivered a version of these remarks at a workshop in Washington DC organized by Arizona State University’s Institute for Humanities Research. Zachary is a professor of practice in ASU’s School for the Future Innovation, in Tempe, Arizona, and the author of The Diversity Advantage: Multicultural Identify in the New World Economy (Westview) and Married to Africa: a love story (Scribner).