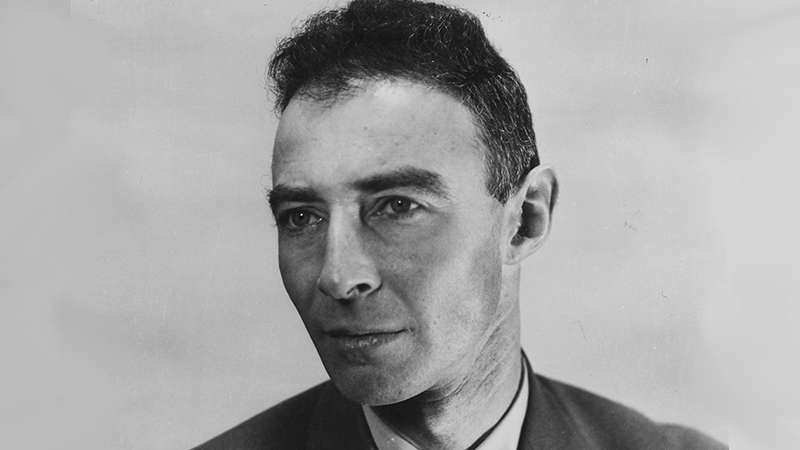

I noticed the physical resemblance between Charles Oppenheimer and his grandfather, physicist Robert J. Oppenheimer, immediately when we sat down for an interview over Zoom. As our conversation unfolded, I learned they also share a fierce commitment to the same ideals and values. Now the subject of a major motion picture, his grandfather’s legacy has reinvigorated conversations about nuclear energy and international cooperation. Charles, through his work at the Oppenheimer Project, hopes to encourage these discussions, advocating for increased energy production and decreased threats from nuclear weapons.

The Oppenheimer Project, which Charles founded in 2019 after a successful career in tech, is dedicated to promoting his grandfather’s values and ideas. Groups like the Atomic Heritage Foundation and the Robert J. Oppenheimer Memorial Committee are actively involved in preserving the Oppenheimer legacy and the Oppenheimer Project hopes to be the genealogical mouthpiece to carry on the task of building post-war consensus and living peacefully and safely with atomic power. “Why doesn’t our family have their own representation for my grandfather?” he kept asking himself.

Charles Oppenheimer and his family have gone on record repeatedly describing their complicated reactions to Chris Nolan’s sweeping epic of their brilliant, capable, but often anguished grandfather. Charles acknowledges the power of having his grandfather’s story as a catalyst for a debate about the role of scientists in geopolitical discourse, and a renewed interest in the peaceful uses of atomic power. He laughingly says he’s thought about quitting giving interviews to the press but knows that he needs “to strike while the fire is hot.”

Post War Nuclear Energy

In the race to decarbonize our energy systems, nuclear has the shakiest reputation but incredible potential, says, Charles. Solar and wind power are variable and intermittent. Hydrogen is still hard to scale. Carbon capture is also still experimental and difficult to scale. But nuclear power, he holds, is a well-known commodity, with decades of science on its side.

Recapping a brief history of post-war nuclear power, Oppenheimer recounts a promising technological story, thwarted by politics. “There was quite a flourishing of support for nuclear energy in the 1950s”, he says, “and there was funding for large energy reactors created to commercially generate electricity.” All this despite an escalating cold war with the Soviet Union and others. “Reactors to provide energy were being built right in the depths of the arms race with other countries. At the same time, we were keeping secrets and spying, he says, there was actually a concerted effort internationally to share and disseminate and cooperate on fission energy.

Interested in learning more about climate science & energy solutions at scale? Join us for Techonomy Climate NYC.

During the Eisenhower administration, groups like Atoms for Peace were created with impetus from J. Robert Oppenheimer to acknowledge the risks and hopes and of nuclear energy and answer the public’s fears about atomic power as a force of destruction. With backing from the U.S. government, large (and costly) reactors were built in the 60s and 70s. To this day, we produce 20% of our energy in the U.S. from nuclear.

But accidents like Three Mile Island (1978), Chernobyl (1986) and later Fukushima (2011) made the public wary of nuclear energy. Statistically, fatalities and on the job injuries sustained at nuclear reactors are low compared to coal and hydro-electric plants. But between bombs and plant meltdowns, public opinion has been tainted against thinking of nuclear energy as a viable alternative to other renewables. Other cons include enormous costs along with how to safely retire, transport and handle nuclear waste.

Oppenheimer encourages us to look at the data to explain the nuclear story. “You can talk about fear and media perception, and then you can talk about things that you can measure, like how many people got sick. If you were going to use facts to measure it, it’s turned out to be one of the safest, cleanest possible sources of energy that’s based on gigawatts produced.” The fear, he says, “never matched the facts.”

One of the things that the U.S. did famously wrong in the heyday of building large nuclear plants, says Oppenheimer, is that we didn’t do what France did, which really centered on refining one reactor design and using it across the country. Instead, he says, the U.S. experimented.

Renewables like solar and wind are important, says Oppenheimer, but the investment hasn’t yet measured up to the amount of carbon freedom gained. He points to Germany as a country that’s made a huge investment in renewables, but still relies on fossil fuels for a majority of its energy.

There is no one silver bullet to producing alternatives to coal, but Oppenheimer believes fusion-based nuclear power should play an important role in the mix. “It is proven science and engineering, and we know it’s scalable.” He is particularly excited about the idea of smaller, efficient and mass produced reactors called SMRs (Small Modular Reactors) and their smaller counterparts, microreactors. These, he believes, can be mass manufactured at affordable prices. “With new engineering techniques to create smaller reactors you could start stamping them out, factory-style with great efficiency.”

As for the required uranium supply, Oppenheimer says that it’s one of the most plentiful resources in the world. “It’s not like the rare minerals that go into our cars, our electric vehicles and our renewables. There’s enough uranium to power the world for millions of years.”

The Summer of Climate Goes Nuclear

Somehow, it’s fitting that the 2023 summer of climate change: forest fires, hurricanes, extreme heat, flood and droughts, was also the summer that brought the story of the original planet killer, the A-bomb, to the big screen. Oppenheimer relates the two. He told me that he lost his own home in the Lahaina fires in Hawaii, reaffirming his belief that the time to act is now.

At its essence, the Oppenheimer Project is about “worldwide cooperation in dealing with existential threats.” Charles often gets asked if he thinks the United States can sit down at the table with Russia, India, China, and other countries and agree to talk about nuclear energy and climate change.

“We all have weapons; they’re all pointing at each other. It is difficult to discuss things with people who have diametrically opposed views to yours, but there are things we can agree on. Energy is one that is really easy to agree on,” he says. “I can’t promise world peace in every area, but let’s work on the framework we can agree on.” Even in the U.S., where there’s so much polarization, it’s easier now than ever to find political common ground, he points out. Oppenheimer also believes that developing countries will play a big part in adoption of nuclear energy. In the same way that they leapfrogged the world in terms of mobile phone adoption because they didn’t have a landline infrastructure, they’ll skip coal and move to nuclear energy with the right investments.

AI: The Next Existential Threat?

Oppenheimer says he gets a lot of questions about what his grandfather would say about AI. “Humans are always creating some version of science and technology. And that will always pose a threat,” he said. “So, what did we learn last time and what can we do this time around?”

Growing up in the shadow of both the greatness and flaws of his famous grandfather, Oppenheimer says he never felt pressure to follow in his footsteps, nor right the world’s wrongs. “On the other hand,” he says, “there was an idea that one of the most important things in the world was the threat from nuclear weapons. That threat felt real, and quite personal to me.”

Another core question: should we do science even when it poses a danger? “My grandfather gave a clear answer on that. We must do science.” Famously Robert Oppenheimer said “There must be no barriers to freedom of inquiry … There is no place for dogma in science. The scientist is free, and must be free to ask any question, to doubt any assertion, to seek for any evidence, to correct any errors.” His grandson and the Oppenheimer Project intend to carry on that legacy.

Techonomy Climate NYC: Solutions That Scale

This in-person event in NYC focus on the business of fighting climate change bringing together climate experts, industry giants, entrepreneurs, and other leaders.

Register Virtual Only