Home to the Charleston Symphony and host to frequent performances of opera, dance, theater and music, the Martha and John M. Rivers Performance Hall at Charleston’s Gaillard Center is one of the most beautiful performance spaces in the United States. But on this pleasingly warm night in mid-December, the action at Gaillard is taking place outside, in the building’s courtyard, underneath a charming European-style tent known as the Spiegeltent, where an audience of about 200 adults has gathered to watch a spectacle that really wouldn’t work in the big room.

Tonight’s entertainment is an English burlesque troupe called Underbelly, a group of attractive young men and women, all impressively curvaceous and/or ripped. As one by one they stride across the round, circus-like stage, they are funny, flirty, and bawdy. Before very long, they are also, mostly, undressed—like, for example, the buxom brunette who seductively tosses her black lace bustier over my face. (That’s what you get for sitting front row at a burlesque show.) I peel it off in time to see her clamber into what looks like an oversized martini glass, splashing about in its contents before she deftly scissors over the side and drops cat-like to the stage. Meanwhile, a stagehand has retrieved her bustier from its perch on my shoulder.

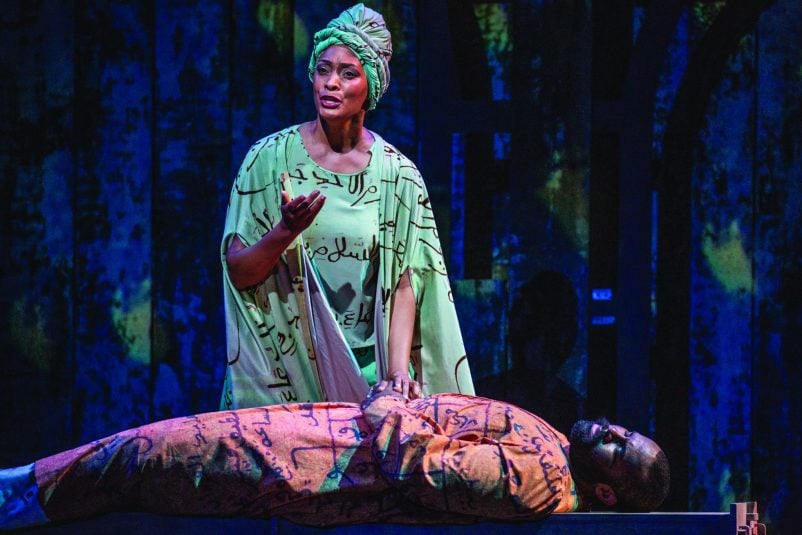

Photo by Amos Adams

You might expect to see such Bacchanalia in New York or Chicago or Los Angeles. But Charleston? When visitors think of Charleston, they think Lowcountry, high culture: The small South Carolina city has become a must-visit destination for lovers of architecture, food and history. Visitors stay in one of Charleston’s many outstanding hotels, tour the impressive Gibbes Museum of Art or the Charleston Museum, shop on King Street, and eat very, very well. Others stay a night or two in town before heading to nearby Kiawah Island or another of the area’s romantic barrier islands.

They do not typically come for burlesque. In fact, until now, they may never have come for burlesque.

But perceptions usually lag reality, and the reality is that Charleston is fast becoming one of the most diverse, vibrant and innovative art scenes in the nation. On any given day or night there, you can hear Charleston’s Emmy-winning jazz quintet, Ranky Tanky, playing at the Gaillard; watch an original performance of Broadway’s The Lehman Trilogy at the intimate, 112-seat PURE Theatre; check out Chris Stapleton and Margo Price at Credit One Stadium; see the work of artist Fletcher Williams III at the International African American Museum; hear a performance by Charleston Chamber Music in the historic Dock Street Theatre; catch a show by rising alt-country group Red Clay Strays at the Riviera Theater, a renovated Art Deco movie palace; participate in an interactive opera by Holy City Arts & Lyric Opera; or visit the stunning gallery of painter Jonathan Green, whose gorgeous work chronicles the power and the story of South Carolina’s Gullah culture. Visitors who wish to embrace art even further stay at the charming Vendue hotel, which showcases the work of local artists and even hosts an artist-in-residence.

And all that is without even mentioning Spoleto Festival USA, a 17-day artistic smorgasbord that takes place in Charleston every spring.

There may be no other American city of its size—Charleston has about 150,000 inhabitants—with an equivalent outpouring of creative culture. And all signs suggest that Charleston’s arts have room to grow.

“Right now, Charleston is a foodie capital,” says Mena Mark Hanna, Spoleto’s general director and CEO. “It’s a destination city. But its next iteration is going to be as an artistic center and a creative capital.”

To understand the origins of Charleston’s thriving arts scene, you have to consider the origins of Charleston itself, the dialectical relationship between the health of Charleston’s economy and the vigor of its cultural life. You also have to appreciate the enduring legacy of slavery in South Carolina and the profound contributions of African Americans.

Founded in 1670, Charleston was a hub of the African slave trade almost from its very beginning. From the early 18th century until the newly formed United States abolished the slave trade in 1808, slavers transported an estimated 125,000 Africans to Charleston, where many would be sold at the now infamous Gadsden’s Wharf.

Most of the enslaved Africans would be forced to work growing cotton, indigo and rice on plantations across the state. Their enslavement was brutal and barbaric; an estimated one-third of the Africans brought to Charleston died within a year of their arrival. But for whites, the slave trade produced wealth unrivaled anywhere else in the colonies. By 1776, according to historian Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, 90 percent of the richest people in the American colonies lived in Charleston.

Seeking to replicate European culture, South Carolina slaveholders used their wealth to patronize the arts. Their homes and plantation mansions were the grandest in the colonies, stocked with commissioned portraiture, imported furniture and Chinese porcelain, protected by wrought iron railings forged by slaves. In addition to the slave trade, the resulting demand for imported goods made Charleston a center of global maritime commerce.

“You cannot talk about American history without talking about Charleston,” says painter Jonathan Green. “And you can’t talk about Charleston without talking about England, France, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Africa.”

The desire of white colonial Charlestonians to fashion a life of ease and sophistication extended into the world of public art; the city’s Dock Street Theatre was the first structure in the colonies built specifically for use as a theater. In 1736, the year of its opening, Dock Street premiered an opera called Flora, thought to be the first production of an opera in the New World. (Most colonists were more concerned with survival than libretto.) The tragic juxtaposition—an economy based on brutality, its profits channeled into high art—can’t be overstated.

The American Revolution and the Civil War challenged white Charleston in physical, psychological and economic ways, and of course the latter finally brought an end to slavery. During Reconstruction, Charleston struggled to recover economically during the transition to a free labor economy. The city’s maritime economy, already waning before the Civil War, declined precipitously afterward. Not until the opening of a naval base in the city in 1901, and the subsequent construction of railroad lines into Charleston, did the city begin to develop a new economic foundation.

In the 1920s, with its population and its economy growing, Charleston entered a period of artistic creativity now known as the Charleston Renaissance. The newly founded Preservation Society of Charleston devoted itself to saving the city’s historic architecture. Local writers were producing works of history, poetry, theater and fiction. Most prominent were Dubose and Dorothy Heyward, who wrote the play Porgy, which George and Ira Gershwin and Dorothy Heyward later adapted into the classic “folk opera” Porgy and Bess.

Perhaps the most influential contributors to the Charleston Renaissance were its painters, especially Alfred Hutty, Alicia Ravenel Huger Smith, Anna Heyward Taylor, and Elizabeth O’Neill Verneer. Focusing on the architecture, landscape and people of Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry, they helped to define Charleston’s identity; their work promoted the city to outsiders and fueled growth in tourism. Many of those who came as visitors would eventually stay as residents.

In the decades after World War II, Charleston’s economy stumbled again, confronting its biggest challenge in 1993, when the federal government closed the nearly century-old naval base. But the most important event in Charleston’s modern history was the 1975 election of progressive Democrat Joe Riley as mayor. A visionary leader, Riley focused on rebuilding the city’s economy while addressing its painful racial history. He would serve ten terms as mayor and play a huge part in the city’s rebirth as a cultural crucible.

For one thing, Riley believed that Charleston should have an arts festival—specifically, an American version of an Italian festival known as Festival Due Dei Mondi (“The Festival of Two Worlds”). An Italian composer named Gian Carlo Menotti had founded the festival in Spoleto, in central Italy, in 1958, and hoped to bring it to America. With its international flavor and appreciation for the arts, Charleston seemed a natural home. Skeptics argued that such a festival would lose money and undercut the local arts community, but Riley loved the idea. “What I knew—what I believed—was that a great arts festival, a world-class, world-renowned arts festival, if it was held here, would produce so many positive changes for the city,” he told the Charleston Post and Courier in 2015.

Riley was right. With funding from private donors, the city, and the South Carolina state government, Spoleto was launched in 1977. Since then, it has become a pillar—probably the pillar—of cultural life in Charleston. For 17 days every May and June, across multiple venues, featuring artists from all over the world, Spoleto typically stages more than 100 performances—opera, dance, theater, music of all varieties. It’s an astonishing outburst of very hard work and vast creative energy. Now, as it approaches its 50th anniversary, Spoleto attracts visitors from around the globe, fosters an artistic ecosystem, and elevates Charleston’s reputation for cultural sophistication.

Spoleto succeeds in part due to its ambition, especially in opera, which is the festival’s mainstay; while Spoleto isn’t afraid to be popular, it is never middlebrow. In 2004, for example, festival head Nigel Redden oversaw the production of The Peony Pavilion, an 18-hour Chinese opera, in Chinese, that required four days to complete. If festivalgoers didn’t like The Peony Pavilion, they could take in performances by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Mikhail Baryshnikov. “Nigel was incredibly adept at pushing the avant-garde,” says Mena Mark Hanna, who succeeded Redden as general director in 2021. “You have an audience that has a thirst for experimentalism because of Nigel’s legacy.”

Hanna, the founding dean of Berlin’s Barenboim-Said Akademie, is continuing that tradition while adding his own priorities: challenging the legacy of colonialism in high art and fostering inclusion at every level of festival production. He was an ardent champion of the opera Omar, based on the life of Omar Ibn Said, an enslaved Muslim from West Africa transported to Charleston in 1807. Originally commissioned by Redden, Omar was potentially awkward for Charleston—after all, Said was sold on Gadsden’s Wharf, about a mile from where the opera premiered. But Omar played to packed houses and won rave reviews, winning the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

This year Hanna is producing the world premiere opera Ruinous Gods, about the heartbreaking journeys of refugee children. “It’s a very difficult piece, but it’s told so beautifully that it draws you in,” he says. Hanna looks for art that has a timeless quality, and he thinks Charleston helps provide that dimension. “You’re going to see something modern and provocative, but afterward you’re walking along 300-year-old streets,” he explains. “There is magic in that.”

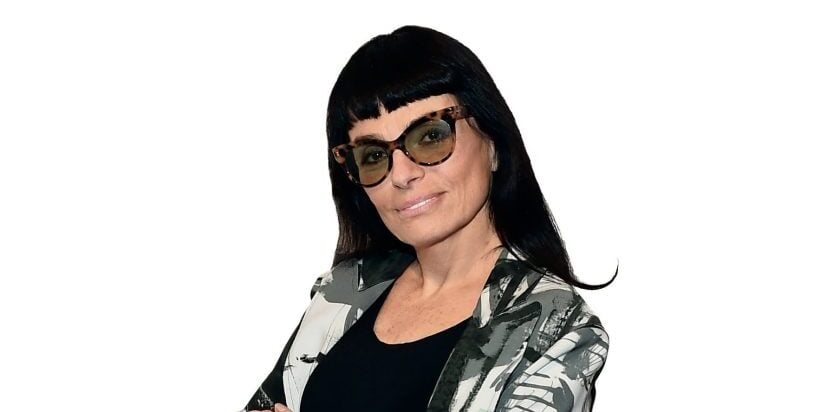

Much of Charleston’s cultural boom stems from the fact that the city embraces newcomers. It’s a self-confident place that isn’t afraid to reach out to larger cities to attract talent. Simultaneously, Charleston has become an enticing locale for creative types who want to escape big city stress but still live somewhere where the arts are practiced at a high level. One example is Lissa Frenkel, president and CEO of the Gaillard Center, who came to Charleston in 2021 after running the Park Avenue Armory, an experimental performing arts space on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

“What I experienced when I came down here is that the community was exploding in growth,” Frenkel says. “There was this huge amount of people coming into Charleston from all around the country because it has this artistic reputation, and you can come and see artists that you expect to see in New York and Los Angeles.”

Leah Edwards, who, with her husband Dimitri Pittas, founded Holy City Arts & Lyric Opera in 2020, came to Charleston from New York in 2015. Both were successful singers there, Edwards in Broadway roles and Pittas in opera productions throughout North America and Europe. “We came down here for 48 hours in January—it was 65 degrees and there were dolphins jumping in the bay,” says Edwards. Charleston felt to her like a place where you could raise a family in a safe and nurturing environment, while also being a city that could support the fledgling opera company she and Dimitri wanted to found. They soon returned to stay.

Sharon Graci, who cofounded PURE Theater in 2003, made her way from western Pennsylvania to Charleston, where she met her husband (and the other PURE cofounder) Rodney Lee Rogers, a filmmaker from North Carolina. “I think the living’s a little easier in this little Eden-by-the-sea,” says Graci. “And if you are into the arts, you will find an outlet for that love here in Charleston.”

Beyond that influx of new energy, a city’s artistic scene requires other crucial ingredients: devoted benefactors, engaged audiences, performance facilities, community leadership, and the support of city government. Charleston has those attributes and one more: a knowledge that it can, and should, tackle the most difficult subjects. Even before the racial unrest that swept the country in 2020, Charlestonians recognized that their city had a moral obligation to address its past; Joe Riley, for example, began promoting the idea of an African American museum in 2002. The 2015 mass shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church served as a tragic reminder that the past never really goes away, but the fact that the city didn’t erupt in violence following the shooting testified to the amount of racial healing that had already begun. The arts community had—has—its own part to play.

At PURE, says Sharon Graci, “we did not need the tragedy of George Floyd to remind us that our communities are made up of more than the typical demographic of who comes to the theater. We program for how Charleston looks.” One recent example: a production called The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, a play about race, capitalism and professional wrestling. At the Gaillard Center last fall, Lissa Frenkel produced Finding Freedom: The Journey of Robert Smalls, the story of a South Carolina man born into slavery who escaped bondage during the Civil War and later won election to the United States Congress. With the help of local sponsors, the show was performed gratis before 6,000 low-income students from regional schools.

When Charleston insurance executive Lee Pringle decided in 2012 that he wanted to create a classical music orchestra featuring only Black musicians, “I was focused on how much my ancestors had contributed to the genre of classical music—but weren’t seen as contributors.” Now the Colour of Music-Black Classical Musicians Festival has been performing in Charleston and cities around the country for over a decade. Occasionally, Pringle gets asked why all his performers are Black—wouldn’t it be enough just to have an integrated orchestra? But Pringle is determined to show audiences the depth and breadth of Black classical musicianship. And “because Charleston has such a unique place in American history, I didn’t want my mission to focus on anybody but the people from my community.”

Among many other productions, Omar and the upcoming Ruinous Gods demonstrate how Spoleto can challenge its audiences. But Hanna emphasizes that controversy is not an end in itself. “You don’t want to be transgressional just for the sake of being transgressional,” he says. “You also want to capture the incalculable joy of human expression.” A festival like Spoleto, he says, should prompt conversations that aren’t defined by our political trenches. Often, you do that simply by making people feel. “Art is about the irrational expression of love, joy, humanity and transcendence,” Hanna says. “It makes our heart skip a beat.”

I thought about that while at the Gaillard for a winter performance by students from the Charleston County School of the Arts, a respected arts academy whose graduates populate Charleston’s cultural life. On stage, performing holiday music before a sold-out house of families, friends and fans, the young musicians and singers were strikingly poised, their youth belying their expertise. At one point the conductor announced that, before the next song, the audience would have to learn a bit of sign language—holding hands high, palms facing out, wiggling them back and forth to signify clapping. Then about a half dozen young men and women, all deaf, took center stage. Guided by teachers standing amidst the audience, they signed the glorious hymn “Silent Night” while the student orchestra played its music.

When they finished Silent Night, the audience leapt to their feet and raised their hands in love and wonder. As the performers smiled and looked bashfully at their shoes, the silent applause continued on and on and on. Here in Charleston, our hearts had skipped a beat.