Climate change is critically impacting the American West and along with it agriculture.

In particular, the Colorado River Basin is undergoing a dramatic transformation. Climate change projections suggest overall water flow there is likely to drop between 10 and 30 percent by 2050. Yet the Basin supports $1.4 trillion in annual economic activity and 16 million jobs across California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming – equivalent to about one-twelfth of the total gross domestic product in the U.S. If 10 percent of the River’s water were unavailable it is estimated that there would be a loss of $143 billion in economic activity and a decline of 1.6 million jobs in just one year.

The Colorado River Basin also supplies more than 1 in 10 Americans with some, if not all, of their municipal water, including drinking water. The Basin provides irrigation to more than 5.5 million acres of land and is essential as a physical, economic, and cultural resource to at least 22 federally recognized Native American tribes.

It has become clear, however, that under current and projected conditions, the Colorado River is no longer able to meet the demands of its many users. In fact, it has recently been estimated that the River’s water use will need to be cut down by as much as a quarter to avert the looming crisis.

Implications for Agriculture

With the immense strain on the Basin come implications for state economies, and in turn, agriculture. The pain is already being felt, in particular in Lower Colorado River Basin states Arizona and California.

According to a publication from the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, among the top agricultural products to be impacted by increasing droughts and hotter temperatures are vegetables, cattle (and livestock, in general) and dairy. The American Farm Bureau Federation points out that drought is hugely significant in the region given that Arizona’s primary land use is livestock grazing, with more than 6,000 cattle ranches covering almost 75% of its land area. Due to lack of rain, ranchers are hauling in virtually all the water that they are no longer able to get from pumps or pipelines. They’re selling off portions of their livestock, as a result. Crop production also struggles in the severely dry conditions.

And that’s only in Arizona. It goes without saying, the state is not alone.

A March article by the Washington Post also illustrated the impact of the so-called drought, pointing out that California has a nearly $50 billion annual agriculture industry, and the Central Valley there alone produces around eight percent of the nation’s fruits, vegetables, dairy products and other food, according to the federal government. That translates into roughly a quarter of the nation’s food and 40 percent of its fruits and vegetables. Farmers just in the Westlands Water District in Central California produce nearly $2 billion worth of food and fiber crops annually.

As the severe conditions shrink one of the most crucial agricultural economies in the country, it’s time to rethink how we view and act on the issues at hand.

The issues of water, climate change, and agriculture can no longer be ignored and viewed as separate issues. We must rethink outdated public policy frameworks for how we manage water and agriculture. An integrated strategy for watersheds and foodsheds is needed.

The Potential Paths Forward

First we must accept that the 1922 Colorado River Compact that governs relations among the states that rely upon the watershed is no longer able to address the aridification of the American West. As temperatures continue to rise, river flows will continue to decline. These challenges are beginning to be understood by public policy leaders. Most recently, former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt made headlines for declaring that a new Compact is needed to address Western aridification, a change from his previous position that the current Compact should remain in place.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation looks to reinterpret the law instead of rewriting it and will begin to work on a post-2025 operating plan for the Colorado River Basin. Its view is that it’s necessary to rethink how states interpret the Compact’s existing language and set new definitions going forward. Those adjustments could ensure the seven Basin states share the burden of a smaller river equally, avoiding potentially significant cuts to water use in the upper basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. (The lower basin states are Nevada, Arizona, and California.)

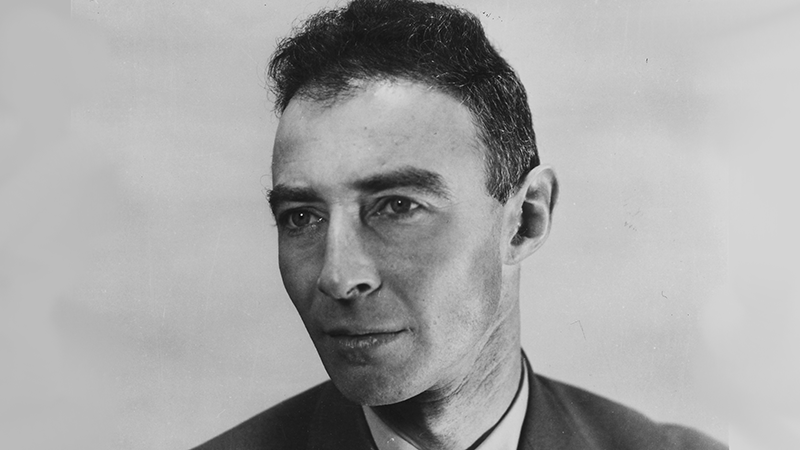

The second part of an integrated strategy should be more radical. It would be to govern water within watershed, rather than state, boundaries. This was first proposed by John Wesley Powell, the second Director of the U.S. Geological Survey, in his map of the “Arid Region of the United States,” presented to the U.S. Senate in 1890. This map presented what was even then a radical new vision of the American West, centered on watersheds rather than on traditional political boundaries. It was the country’s first ecological map, building on, but pushing far beyond, earlier efforts that century.

The third potential path is to view agricultural production as well as water resources as national security issues, and thus managed beyond political boundaries. State boundaries are poorly designed to manage water and agricultural production in a sustainable manner. Combining Powell’s watershed framework for managing water resources and overlaying “foodsheds” is a path forward. This third framework will be a challenge, to say the least. However, this is the kind of thinking we need to address the impacts of climate change on water resources and agricultural production.

The Colorado River Compact needs an immediate overhaul to integrate current climate modeling with integrated state-level strategies for agricultural, energy, economic development and ecosystem conservation. The Compact needs a reboot to align with current realities. This won’t be easy, but the ongoing collision of the status quo with outdated public policy will, if we don’t act, inevitably be more painful.