In this talk from Techonomy 2011 in Tuscon, Ariz., Jared Cohen, Director of Google Ideas, discusses how Egyptians used the Internet to advertise and broadcast their revolution, and how it affected the outcome of the uprising. Had Mubarak not shut down the Internet and mobile service networks during the uprising, says Cohen, he might have had a better chance of staying in power.

Cohen: Now, what’s interesting is if you go to Egypt—which happened about a month after Ben Ali fled Tunisia—the Egyptians had a different tactic, which is they actually advertised their revolution. Now whether or not technology and this organizing online was what made or broke the revolution is less important than the fact that they put it all online in advance. Have you ever heard of advertising a revolution or advertising a mass-mobilization? The only time that I’ve heard of something quite so concrete was in 2007 during the coup in Fiji, and I’ll never forget a story: I came into the office and found out that the coup had been moved because the coup leader’s mother-in-law’s birthday was taking place.

But this was unlike anything that we’d ever seen before, and what’s interesting is the two tools that were used to organize the revolution in Egypt—one of them arrived in Egypt in the seventh century: the mosque, and one of them arrived in Egypt in 2007, which was online social networks. And these two tools brought together two different sets of demographics. And because they advertised it and because they put it all online the revolution had two fronts: it had a virtual front and it had a physical front. And it invited transnational meddlers to come into the mix—diaspora communities, young people around the world who felt like they sympathized with the young people of Egypt.

Now, what’s interesting in Egypt is Mubarak did not learn the lessons from Ben Ali and others—he shut down SMS, he shut down the Internet. I was in Egypt coincidentally at the time of the revolution and I talked to some young people there and learned some very interesting facts. When I asked one young person why he went to the street he said, “This wasn’t my fight, but then Mubarak took away my internet and took away my access to mobile devices and he made this relevant to me. I wouldn’t have gone to the street if he didn’t directly go after the things that I use every single day.” I talked to another person who said, “What was I going to do, sit at home in my house with my internet that didn’t work and my mobile device that didn’t work, and it was too hot and I couldn’t do anything else so this seemed interesting.”

Which made me realize that revolutions going forward and acts of citizen empowerment and grassroots movements are inherently social, right? Where young people have websites instead of offices, they have followers and members instead of paid staff and they use publicly available platforms instead of applying for budgets from foundations, and they go where their friends go. But the other interesting piece from Egypt is I actually think had Mubarak not shut down SMS and not shut down the internet, there’s a better chance that he actually would have stayed in power. Now, I’m not passing a judgment good or bad, it’s just an observation that if we look at Egypt and Tunisia shutting down the internet does not work.

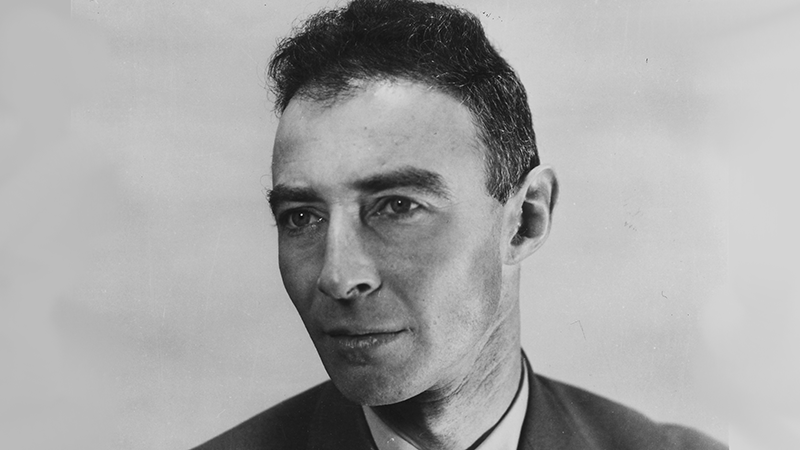

Jared Cohen of Google Ideas on How Egyptians Networked Their Revolution

In this session from Techonomy 2011 in Tuscon, Ariz., Jared Cohen, Director of Google Ideas, discusses how Egyptians used the Internet to advertise and broadcast their revolution, and how it affected the outcome of the uprising. Had Mubarak not shut down the Internet and mobile service networks during the uprising, says Cohen, he might have had a better chance of staying in power.