The recent explosion of environmental, sustainable and governance (ESG) investing has created a lot of opportunities for investors and financial institutions. The adoption of the Paris Accord and their recent amplification in Glasgow, along with the election of Joe Biden in the US, have accelerated the already-growing trend toward ESG. Annual cash flow into ESG funds has grown tenfold since 2018, and ESG assets under management are expected to account for one-third of all investments worldwide by 2025, or approximately $53 trillion.

But this massive shift also represents a set of profound data challenges. With no universally-accepted definition of ESG, how does anyone measure performance? And with more companies and countries promising to reach carbon neutrality by a given year, how does anyone measure whether they are actually keeping up, much less standardize that performance across industries and national boundaries? The capture, organization, and modeling of data are too complex and too expensive for the vast majority of organizations to do on their own.

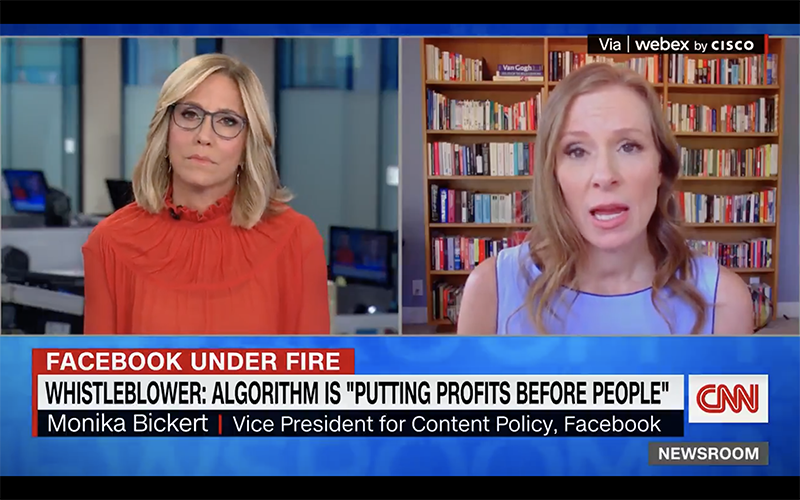

ESG’s data challenges were the topic of a recent Techonomy virtual salon hosted by Red Hat, and moderated by James Ledbetter, Chief Content Officer of Clarim Media, parent company of Techonomy. The salon explored the roots of recent developments in ESG, how institutional players are tackling the new data challenges, and where the data approach to ESG is headed.

Richard Harmon, vice president and global head of financial services at Red Hat, asserted that the company’s Linux/open source background lends itself well to the ESG data challenge. “From the roots of the open source community, open culture, which we [at Red Hat] have, topics like climate change and the wider ESG framework are natural things for us to dive into.” He noted that Red Hat had joined a consortium called OS Climate, launched last year by the Linux Foundation to “address climate risk and opportunity in the financial sector.” It currently includes Amazon, Microsoft, Allianz, BNP Paribas, Goldman Sachs, and KPMG among its member base. This broad group of companies–many of which compete with one another–is necessary, Harmon said, because the “volume and complexity of the data that needs to be utilized is unmatched.”

Lotte Knuckles Griek, head of corporate sustainability assessments at S&P Global, explained that she has been measuring company performance on ESG metrics for 15 years, with the company being involved in ESG ranking since the beginning of the 21st century. The tremendous growth in the sector, she added, has shifted the stakeholders that S&P serves, which presents a challenge on how to present data in the most useful way. “There’s a huge variety of investors out there looking to consume ESG data, and do very different things with them,” Griek explained.

Some of the changes in recent years have been driven by changes in regulation and government policy. For example, in the United States the Biden Administration seems to favor some kind of uniform definition for what constitutes ESG investment. In Europe, the European Central Bank has already shifted the criteria for it massive pension investments toward “green bonds,” which in turn gives individual countries and companies an incentive to embrace ESG goals.

For her part, Griek said that she always welcomes new government standards and regulations, because they help draw attention to important ESG issues. “But it also totally raises the complexity faced by companies, ”she continued. “One framework says report data in terawatt hours, another says report in megawatt hours…all these frameworks tend to cause confusion.”

Andrew Lee, Managing Director and Global Head of Sustainable and Impact Investing at UBS Global Wealth Management, put the data dimension into a broader context of how UBS (and other institutional investors) serve their clients, who are increasingly interested in sustainability. “Data doesn’t necessarily drive a determination of what’s sustainable or not, for us,” Lee said, explaining that UBS clients or other investors are ultimately seeking transparency into how their money is being invested. “Data is a critical input into a process that looks at how sustainability can be incorporated into investments.”

One topic that recurred through the discussion is the need for data that not only captures performance to date, but that can be used to make reliable models for the future. Lee noted that, while everyone in the ESG ecosystem praises the idea of standardization, business imperatives require something beyond standardization. “As an investor, you want a little bit of standardization, but you want to create alpha, right?” (Creating “alpha” is a way that investment professionals describe their competitive advantage.) “So certain things in your process, maybe it’s the forward-looking data or how you interpret that, give you that edge or ability to outperform.”

In the end, Harmon stressed the need for world-class analytics capability. “That’s what we see as the real differentiator, to solve this global problem that we’re all facing.”