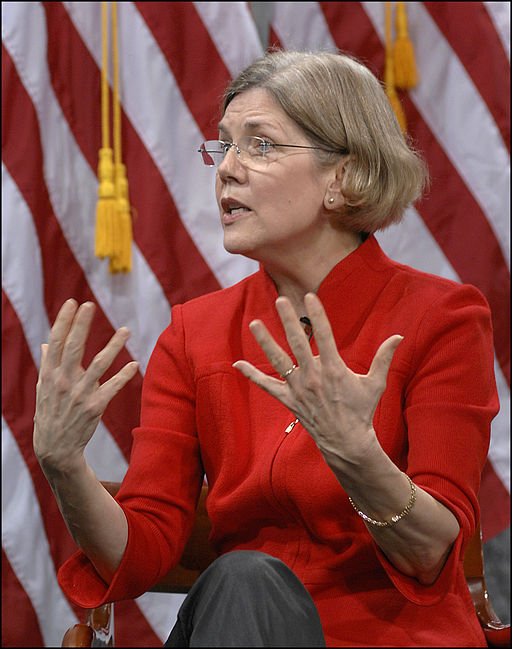

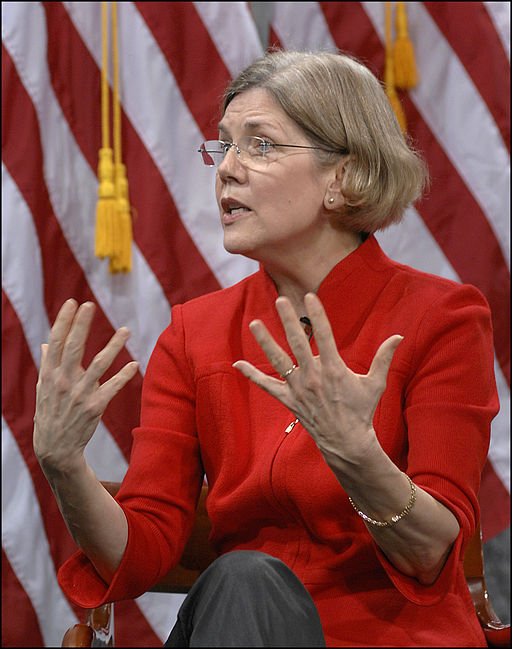

A new bill introduced by Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Mike Enzi (R-Wyo.) would add important privacy protections for genetic data generated by federally funded scientists or housed in databases maintained by federal agencies. The goal is to protect the unique information contributed to these studies by research participants who expect their data to remain confidential. Even if the bill passes, though, there are still a number of situations in which genetic data isn’t protected—and some leaders in genomics are now saying that full protection of this kind of information may not even be possible.

People have two primary concerns about the misuse of their genetic information: discrimination and inappropriate access. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, passed in 2008, was the first major step in establishing federal protections to ensure that people could not be treated differently based on their DNA data. GINA focused on health insurance and employers—the two biggest opportunities for genetic discrimination—but still leaves people vulnerable in areas like long-term care insurance and life insurance, among others.

The newly submitted Genetic Research Privacy Protection Act aims to prevent access to genetic data by people for any purpose other than scientific research (law enforcement or civil suits, for example). Thus far, genetic information produced through federally funded research has typically not been covered under existing privacy laws designed to protect medical data. In the current environment, the senators note, it may be possible for people or organizations to access this kind of information using Freedom of Information Act requests or other legal mechanisms. Once accessed, there would be no way to protect information that research participants expected to stay private.

If this bill is enacted—and that’s a big if, given that it took the much-needed GINA a dozen years to secure enough votes—it would make this data exempt from FOIA requests and extend confidentiality coverage to federally funded scientists so they couldn’t be legally compelled to release genetic information collected in their studies.

“To help to bring forward the next generation of precision medicine, researchers are collecting more and more genetic information,” Warren said in a statement. “When that genetic information is stored at our nation’s research institutions, families should have complete confidence that it will remain private.”

With its focus on research, this bill extends no protection for genetic data produced by the growing number of consumer services (for example, 23andMe). While genetic information generated through medical tests is covered by health information privacy laws, services that use genetic data to reveal ancestry, athletic prowess, or other non-clinical applications are not currently covered by privacy laws specific to DNA data. With more and more people signing up for these services and with lingering uncertainty around privacy and discrimination laws, this is a critical area for legislators to tackle.

It’s worth noting that the very catalyst for this new bill is also the reason the whole privacy issue might be moot. Several scientists have now proven that it’s possible—easy, even—to identify supposedly anonymous research subjects using their genetic data and minimal other information. In one landmark study, researchers figured out the identities of anonymous genomes by using publicly available information from genealogy databases in combination with snippets of DNA data to link last names to the genomes. While that study was cited by the senators as evidence of the need for this new bill, some genome scientists argue that it is instead proof that there’s no such thing as privacy in the genomic era. Unlike research studies that round up a bunch of participants and collect, say, cholesterol levels and blood pressure readings—data that could never be traced back to a specific individual—each genome is unique and by definition can identify the person who contributed it.

Eric Schadt, founding director of the Icahn Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology at Mount Sinai, published a commentary on this topic in which he concluded that anonymity simply cannot be guaranteed for genetic data. “I believe education and legislation aimed less at protecting privacy and more at preventing discrimination will be key,” he wrote. “We must inform patients on what is happening in biology and medicine today and explain why high-dimensional data we collect as researchers cannot really be completely de-identified.”

But as there’s no telling how DNA data could be used or misused in the future, it’s still good to see that at least some government officials are doing their best to ensure basic protections for the public. And in an age of fractious politics, it’s refreshing that both parties came together to present such a bill.

Senators Seek to Legislate DNA Privacy—But Is It Really Possible?

A new bill introduced by Senators Elizabeth Warren and Mike Enzi would add important privacy protections for genetic data generated by federally funded scientists or housed in government databases. It aims to protect research participants who expect their data to remain confidential. Even if the bill passes, though, the genetic data may not always be protected. But some genomics leaders now say full protection may not even be possible.