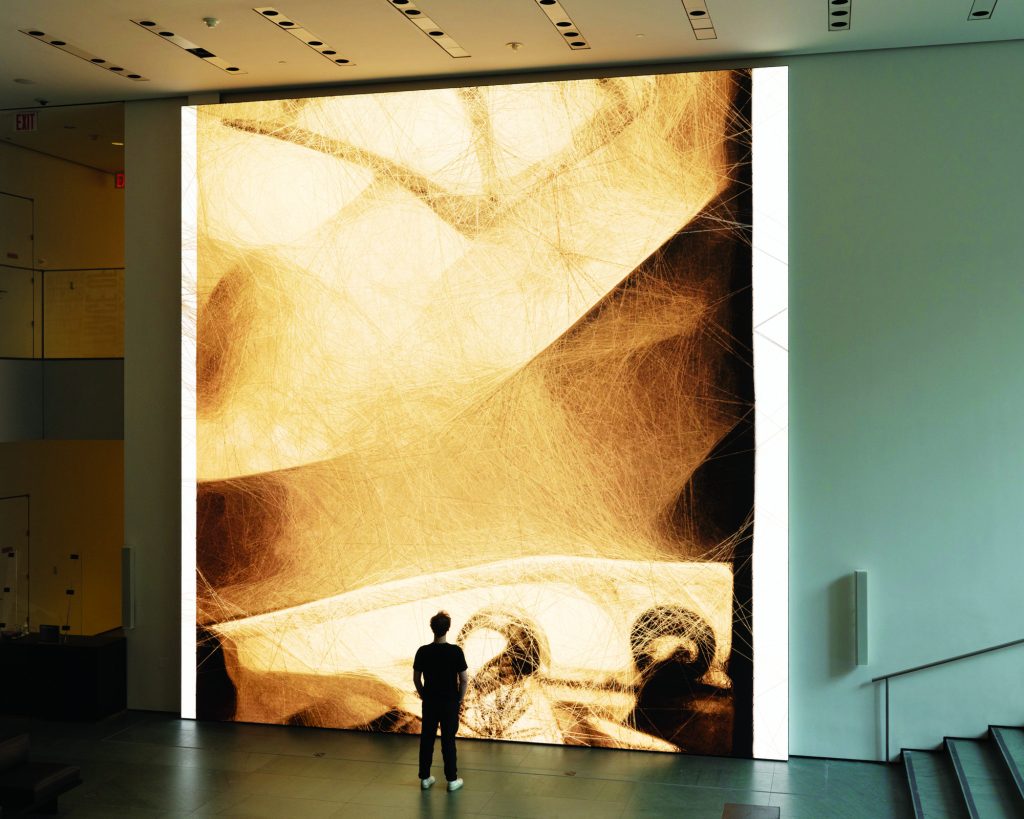

For some people, “Unsupervised —Machine Hallucinations— MoMA, 2022” is a mesmerizing, profoundly beautiful and constantly evolving new art form. For others, like art critic Jerry Saltz, it’s derivative, digital merriment, akin to a massive techno lava lamp.

For “Unsupervised,” Refik Anadol, a Turkish American artist, trained a machine learning model to interpret and reimagine data on all the art in MoMA’s collection. For the 10 months that the site-specific installation was on display in MoMA’s lobby, until it was taken off view in October 2023, it certainly attracted a lot of attention, both from art critics and museum goers.

Visitors stood or sat, sometimes for hours at a time, looking at the constantly morphing and shifting installation, which also responds to changes in light, movement, sound and the weather outside the museum. New forms were continuously generated on a 24-by-24-foot digital screen. Given that the average museum visitor spends about 30 seconds in front of an artwork before they move on, according to MoMA, “Unsupervise” created a stupendous amount of engagement.

MoMA’s First AI Acquisition

In October, MoMA announced that it had acquired “Unsupervised” for its permanent collection. The acquisition was made possible because of a joint gift by Ryan Zurrer, through his own 1OF1 collection, and by Pablo Rodríguez-Fraile and Desiree Casoni, through the couple’s RFC Collection.

It is the museum’s first acquisition of a work created using generative artificial intelligence and a bold move, even for an institution that has championed digital artists, and other forms of generative art, for decades.

Andras Szántó, a strategic advisor to museums and cultural institutions, thinks that MoMA’s acquisition of “Unsupervised,” and the validation it provides, will encourage more museums, collectors, and artists to explore such art. “At a very early stage in the game, one of the most important institutions of art is taking this leap,” says Szántó, who also advises Refik Anadol Studio, but was not involved in “Unsupervised.” “I think it’s the beginning of a new chapter for this art form.”

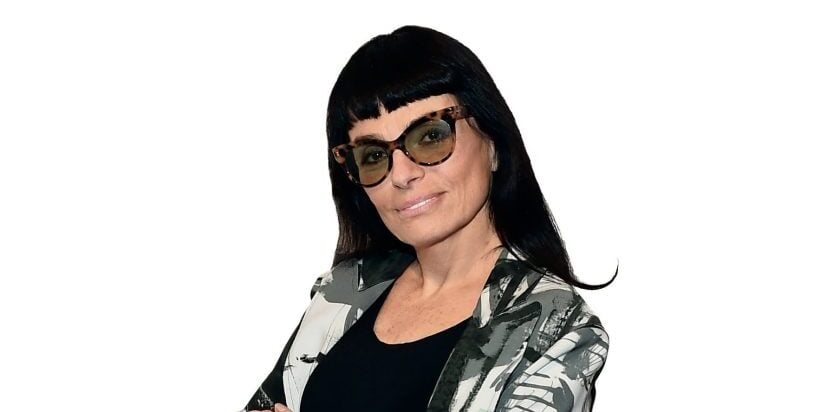

Others are not so sure. Magda Sawon, co-founder of Postmasters Gallery in New York City, established in 1984, has been selling digital art to institutions such as MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Whitney Museum of American Art for over 20 years. She thinks that while this acquisition could raise the profile of such art with the public, with collectors, and with museums, it is not a given.

“Here we have an incredibly high profile acquisition that people don’t want to stop watching when they sit in front of it,” she says. “It does have an impact, but whether it is a trigger to create an enormous field of AI generative art is a big question.”

Other Museums Joining In

MoMA is one of a number of institutions that have exhibited works created with generative AI. Earlier this year, The Denver Art Museum exhibited “Us.” A collaboration between two indigenous artists, poet Jennifer Elise Foerster, and visual artist Steve Yazzie, “Us” combined audio narration with video that used generative AI to draw on artworks featured in “Near East Far West,” one of the museum’s temporary exhibitions.

In New York, “Reconfigured,” an exhibition of works from the Whitney’s collection that closed in June 2023, featured “Im here to learn so :)))))),” a video installation by artists Jemima Wyman and Zach Blas. The work from 2017, which questions the problematic aspects of artificial intelligence chatbots and how they learn, incorporates projections created using generative AI software.

However, Szántó says that most institutions are still not ready to incorporate generative AI into their permanent collections, whatever the context, given how quickly the technology is evolving and the limited amount of museum curators or directors that understand it. “There [is] a limited number of curators who speak this language and even fewer museum directors, who for the most part, didn’t come up in the digital era,” he says. “It will take them a while for the comfort level to be there to really deeply bring this material into museums.”

Could “Unsupervised” inform how other museums incorporate this type of work into their collections, if and when they do? The machine learning model employed by “Unsupervised” uses only publicly available data about MoMA’s art collection, which at least means the data is fairly sourced. That addresses a major ethical sticking point with AI-generated art: that it can be trained using millions of copyrighted images by other artists without their knowledge or consent.

While it seems much more of a celebration of AI than a critique, MoMA’s curators say the installation is a way for the museum to engage with the public debate about what artificial intelligence can and can’t do, or should and shouldn’t do. Anadol created his own AI model for “Unsupervised,” which manipulates existing generative AI programs using custom software to render what people see in the installation. He is an advocate of other artists also creating their own AI models to control the data, the process, and the output.

Anadol also uses unsupervised machine learning in this work, generating something new, a “hallucination,” rather than a regurgitation of the art the machine encounters. It is also a new way of driving visitor engagement and potentially another way to get visitors thinking about MoMA’s vast collection.

Szántó thinks that artworks created with generative AI will eventually become part of a lot of museum collections, just as photography and video and other forms of digital art did before it, but that museums are generally slow to adopt new media, and that validation from scholarship and the art market takes time. “Think of how long it took for photography to establish itself as a museum-ready medium,” he says. “It will probably take a generation for this type of art to comfortably fit in.”

Growing the Private Market for Digital Art

It has taken a long time for the art market to validate the broader universe of digital art, which has been around for decades, because the market still centers around tangible, material objects. “I’ve worked with digital art since 1996, and we have not accomplished what I thought we would because of the resistance to new things and to digital things,” says Sawon.

Trading volumes have slumped since early 2022, but the emergence of NFTs as a new ownership and distribution model has helped to grow the market for digital art, including generative works created with AI. The “Unsupervised” installation, for example, comes with a companion NFT, so that art buyers can own individual artworks based on Anadol’s MoMA project. It means that the installation directly benefits the market for Anadol’s work—and even more unusually, the museum too, because MoMA also receives a cut of the NFT’s primary and secondary sales.

Anadol also uses unsupervised machine learning in this work, generating something new, a “hallucination,” rather than a regurgitation of the art the machine encounters.”

A Second Chance for NFTs

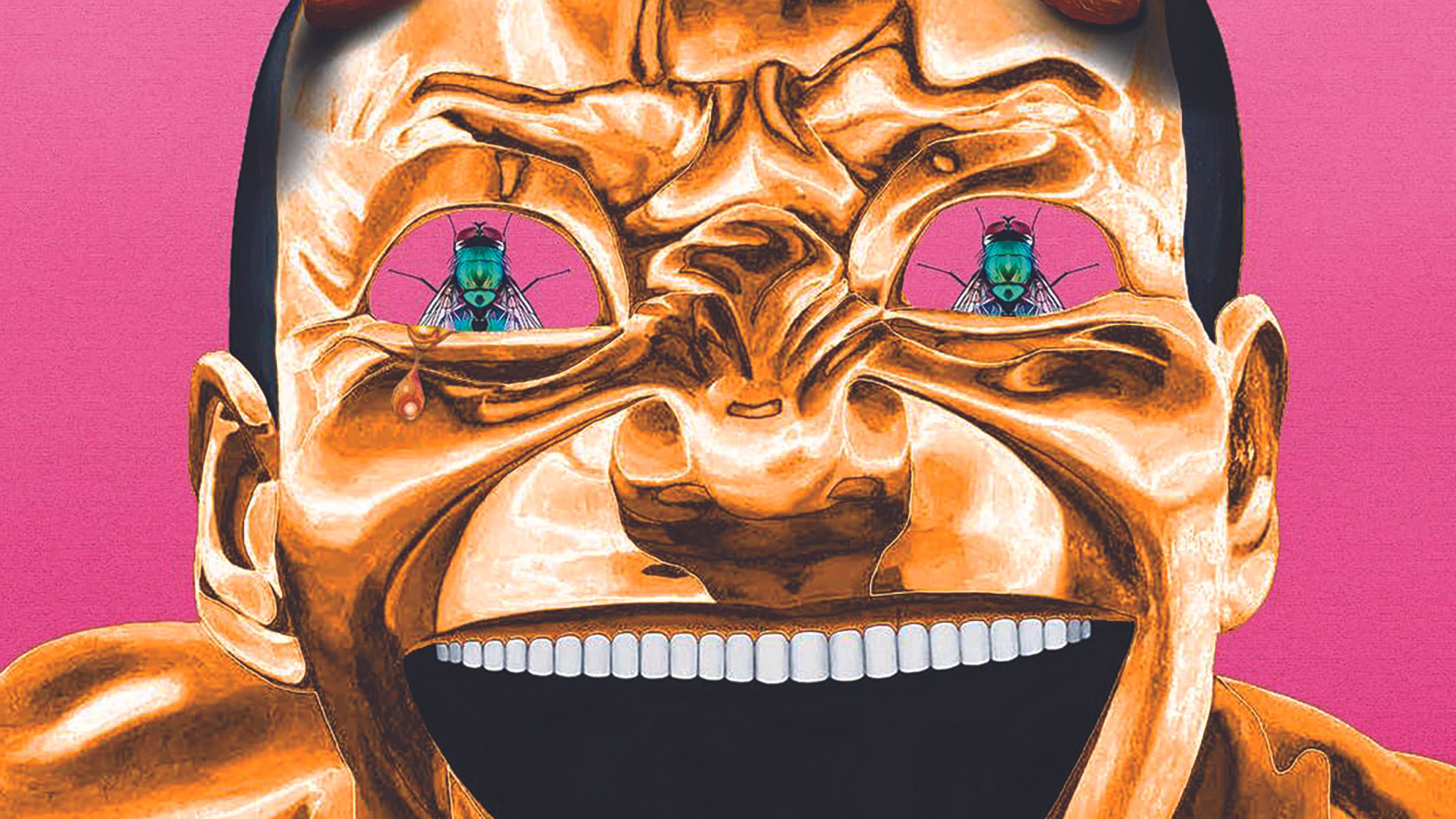

Art NFTs are enabling artists who have never worked in digital media to create and sell works to a large number of collectors. In August, for example, LiveArt, a platform for Web3 art, or art based on blockchain technology, launched “Kingdom of the Laughing Man,” a collection of NFTs by Yue Minjin, one of the top-selling Chinese contemporary artists at auction.

For the first release from the NFT collection, called “Boundless,” Yue Minjin created generative works that are based on his iconic laughing man self portraits. He used generative AI to map hundreds of different graphic layers and then render those in different combinations to create 999 unique versions of his laughing man. The face appears in an array of different colors against a huge variety of backgrounds. In some, he has insects, skulls, or flowers for eyeballs. In others, he appears with horns or other adornments on, or sometimes floating within, the top of his head.

“It’s an opportunity for an artist with an already established career to use an entirely new medium, which is pretty interesting,” says Elena Zavelev, head of marketing and partnerships at LiveArt, and also CEO and co-founder of CADAF, a company that has produced digital art fairs since 2019. Boundless sold out in just two hours, despite the flagging NFT market.

But most NFTs do not feature acclaimed artists, and the volume of art NFTs traded has dropped precipitously since their peak in mid 2021. Sawon works with Kevin McCoy, who created the first art NFT back in 2014, and has also sold art NFTs to institutions like the Whitney. However, she doesn’t think that NFTs have delivered on the promise to showcase all the digital art created over time and put it into the hands of collectors. “There are a few pockets of amazing work that is being purchased by good institutions, but overall I don’t think NFTs delivered on that level,” she says.

Acquiring and owning digital art can still be complicated, but Zavelev thinks that collectors will take a closer look at art created with generative AI now that it has MoMA’s stamp of approval. “I think that collaborations like this one between Refik and MoMA definitely make traditional collectors look more closely at this because they see it, they find it fascinating, and they get more familiar with it,” she says. She adds that even Web3 collectors, who already collect digital art extensively, are looking for confirmation by traditional art institutions that this type work is valuable.

A New Tool for Artists?

MoMA’s acquisition also creates legitimacy for other artists, who may be thinking about using generative AI—if only to confront in their own work some of the concerns that AI generates about copyright, bias, and appropriation, among other issues. “We’re probably going to see a very rapid innovation cycle, partly as the technology accelerates, but also as artists figure out what their agendas are with this set of possibilities,” says Szántó.

For Sawon, though, generative AI is not necessarily going to be a game changer for digital artists. “AI is this huge field of panic, irritation, and fascination, but if you go back to art and artists, it’s essentially just a tool,” she says. “Great artists will use it to make amazing things, but bad artists won’t.”

She also points out that artists creating algorithmic works is nothing new. In May, Postmasters Gallery held a group show called Machine Violence, which featured several digital art pioneers, such as Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, Eva and Franco Mattes, and Miltos Manetas. “The pieces in that show were there precisely to make this argument that algorithmic work, and work that depends on software and certain levels of randomization, were being created 20 or more years ago,” says Sawon.

She cites the example of Horror Chase, an installation created in 2002 by Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, in which the artists reenacted the chase sequence from the movie Evil Dead II on a special set, before digitizing each shot and using custom algorithmic software to create a randomized sequence, with some shots reversed, sped up or slowed down. Sawon says this was the first example of what is now known as algorithmic cinema.

Despite the mixed critical response to “Unsupervised,” it’s certainly been a crowd pleaser at MoMA. It can be quite beautiful, warm, and multidimensional, which is no small feat on a large flat screen. At times, waves and swirls of vibrant, rapidly changing forms and colors appear and disappear, seeming to slosh about within the sides of an enormous three-dimensional frame.

In the end, it is not the technology used, but the work itself, that has appealed to MoMA’s visitors. “Refik is a super innovative artist, and that’s one of the most interesting parts about this, but I’m not sure if the audience knows what’s behind this artwork,” says Zavelev. “I think they are just drawn to the beautiful, ever-changing imagery.”