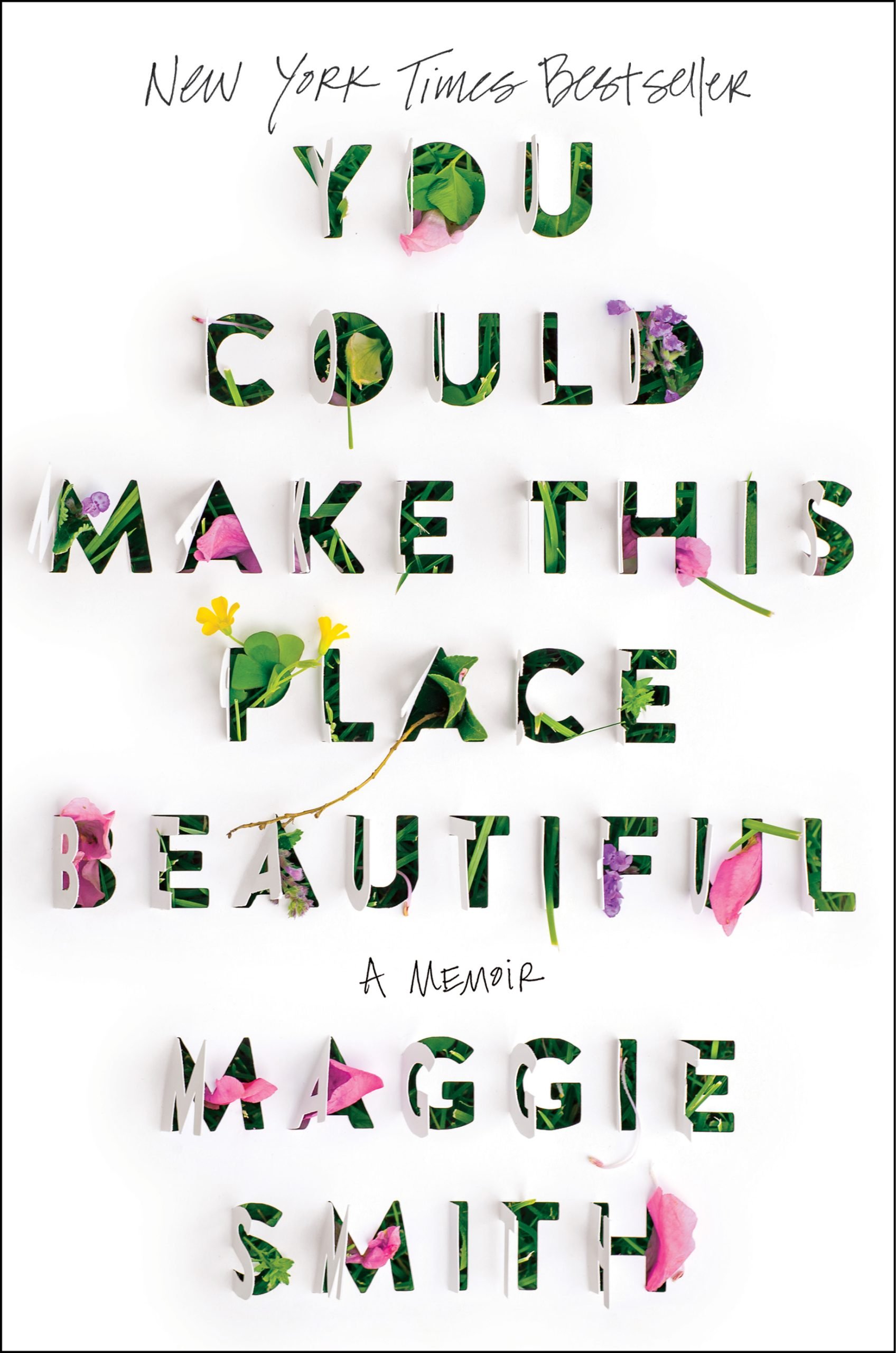

Book: You Could Make This Place Beautiful By Maggie Smith

Once, the poets bound us. With their forceful stories and forthright charm, the Fireside Poets sewed a severed society together with rhyme and myth. Nineteenth Century families huddled in candlelight, united through civil war by the entrancing verses of Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” or Holmes’s “The Chambered Nautilus.” Before telegrams or radio, before screens and scrolls, poetry pioneered virality. Once, poetry was pop culture.

Exactly 150 years after Whittier published “Snow-Bound,” Maggie Smith loosed her mere 17 lines upon the world. Her poem “Good Bones” became a talisman in a season of tragedy upon tragedy, a salve for a nation riven by violence, where the audacity of hope risked its total abdication. Smith’s marvel of form—her seeming simplicity masking her sonic sophistication—dropped a charge into our national waters, sounding our depths, reminding us of the irrepressible irrationality of imagining a better tomorrow.

Prophets and poets, as Smith certainly knows, over-index toward suffering. Truth-telling has its costs. As her poem traversed space and time, giving life and language to aching and adoring multitudes, her marriage was dying. Seven years later, she brings us a document of its decline, its title taken from the final line of her viral poem. She offers her story as neither eulogization nor lamentation, neither investigation nor accusation. Rather, she offers it as any accomplished poet would: as material.

“Love is a kind of literature,” wrote Anatole Broyard. So is–maybe more so–love’s ending. “It is stunning, it is a moment like no other, / when one’s lover comes in and says I do not love you anymore,” writes Ann Carson. Upon that moment, and the bruising moments that follow, a literature of divorce has been constructed. The respective bookshelf is full—of novels (Katie Kitamura’s A Separation), memoirs (Rachel Cusk’s Aftermath), self-help scripts (Debbie Ford’s Spiritual Divorce). The shelf is elastic: Peruse the catalogs of major publishers, and one is certain to spot a new addition to the genre every season.

You’d be forgiven if you shelved Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful alongside them. An easy miscue. If they’re any good, poets stop short of the inscrutable. And Smith has her misdirections at the ready. Her narrative is fragmented. Her timeline loops. Scenes triumph over chronology. On one page, she’s as insistent as late afternoon hunger. On another, she’s drifting and distant as a dream.

The effect is exactly as intended. For anyone who has experienced the dissolution of a family, the fractal nature of Smith’s book is home turf. Fond memories collide with future anxieties. Self-flagellation competes with fantasies of revenge. Fierce loyalty embraces endless adaptability. Swimming between such polarities, Smith freestyles. Sometimes she is a vulnerable guide, in search of her own self-deceptions and self-actualization. Sometimes she is a fearless truth-seeker, excavating the subterranean constructs of gender and power that formed the sandy foundations of her marriage. At all times she is a writer of extraordinary imagination, bringing all the force of her craft—the flaring motifs and abundance of metaphors, the meta-cognitive gestures, the fantastical diversions and sparkling images, the melting tenderness of childhood moments—to bear on one of the most excruciating experiences a human can endure.

A handful of her poems make cameos. “Good Bones” of course. And “Bride.” These moments deliver a kind of relief. From the ongoing trauma and fresh tragedies, from the feelings of alienation and abandonment. Smith’s poems function in this memoir just as they have in her life, and in ours: fragments shored against our ruin, jewels cut from collapse.

Social Media: Threads by Meta

We were young once, and optimists. In the Middle East, revolutions bloomed in the fresh soil of social media, and we called it Spring. In Ukraine, a nation snapped free of the marionette’s strings, amplifying their stories online. We called it a Revolution of Dignity. In the U.S., an American presidential candidate aggregated a coalition through direct exchange, unmediated by cable networks and publishing gatekeepers. We used words like “Hope.”

Twitter facilitated it all. Until that unfortunate law of the internet age proved itself again: Virtues evaporate in the heat of the market until only vice remains. If Twitter once held the remarkable position as the world’s public square, under the leadership of Elon Musk it has been revealed to be less Athenian Acropolis and more Times Square circa 1981. Sure, the buskers are performing beautifully. But behind them a dumpster is in flames, racists are chanting on the corner, and someone is most certainly defecating at the bus stop.

It was inevitable that a competitor would smell bird blood. Mark Zuckerberg—who once proclaimed he would only eat meat that he killed himself—seems to want fowl on the menu. Having succeeded in sub-dividing 3 billion people into echo chambers, creating the world’s most effective disinformation platform, and supporting ethnic violence, Zuckerberg’s misery machine has a new offer: Threads, an app purpose-built to starve Twitter of its last remaining faithful.

“Move fast and break things” was Facebook’s original imperative. “Look around and steal whatever’s working” seems to be its latest mandate. As the saying goes, good artists borrow, great artists steal, and internet moguls copy/paste. Starting with its name—lifted from a particularly popular user behavior on Twitter—Threads looks like Twitter, scrolls like Twitter, and generally works like Twitter. It may be more Twitter like than Twitter itself—now called “X.”

But it doesn’t chirp and float like Twitter. Or at least the way Twitter once did. The Threads app itself is elegant. Familiar design, smooth edges, a pleasant experience one can’t really hate. As a child of Instagram, where masses gather to make museums of their lives, perfect lines were to be expected. But the stripped-down feature set doesn’t amount to “less is more” so much as just less. Notifications are confounding. Search is anemic. Direct messages are non-existent, as are hashtags and trending topics.

The naked nature of Threads isn’t a bug. It’s entirely in line with Meta’s philosophy. While surely additional features will emerge that mimic Twitter’s more delightful and serendipitous dynamics, the fundamental purpose of Threads is different, reflected in its design. Twitter began with earnestness and authenticity in search of profitability. Threads starts with profitability and power in search of authenticity.

It’s not searching very hard. A sub-project of Instagram, Threads isn’t here to generate conversation and debate, to inform and delight and infuriate and shape discourse. By the project lead’s own admission, Threads isn’t here for substance.

A natural extension of a highly active user base on Instagram gave it rocket fuel upon launch. Keeping it in orbit will be ad dollars in need of a home—without the risk of their product showing up next to one of Musk’s free-speech misogynists. But will Threads work for the good of users, correcting past errors and bringing any measure of care for health and society? Doubtful. We haven’t the luxury of choosing a platform run by a noble and benevolent visionary—or even by accidental, well-meaning developers like those that stumbled upon Twitter in the mid-aughts. Musk is chaos, Zuckerberg is a bore, and Threads will not bring spring to any revolutions. We’re too jaded for such hopes anyway. Dignity is beyond us.

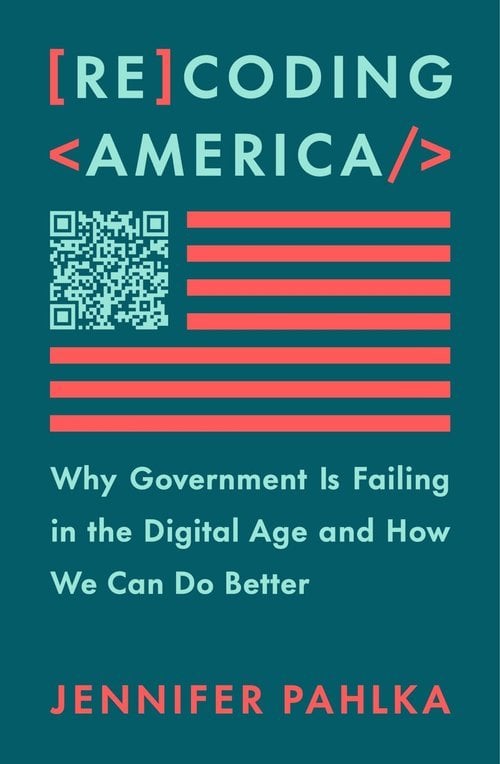

Book: Recoding America By Jennifer Pahlka

Criminally, my friend lost his identity. For half a decade, his name and social security number were linked to an individual convicted of an impressive assortment of misdemeanors and felonies in a city more than 2,500 miles from his home, in a state he had never visited. His attempts to correct the error went as you might imagine. Government phone trees with dead branches. Municipal employees with neither competency nor care. Instructions that, when followed, were said to be incorrect. New instructions that netted the same. More than one voicemail blaming 2020 COVID restrictions for lack of staff—in 2023.

“We get the government we invent,” says Harvard Business School professor Mitchell Weiss. Do we, though? The labyrinthine systems lawyers are required to navigate wouldn’t be the preference of any citizen. (Except perhaps the lawyers.) Opaque processes, indecipherable paperwork, impenetrable layers of desks and plexiglass, inscrutable codes and terms, and threatening notices. It’s hardly what any of us would design, much less what we deserve.

Undoubtedly, though, we get the government someone invented. Jennifer Pahlka has spent a career trying to make sure that someone, wherever they are, works inside a paradigm that builds for “user needs, not government needs.” To enable this work, she founded Code for America, a technology nonprofit aiming to make government services more accessible and efficient, and then went in-house, founding the United States Digital Service in the Obama administration. Said another way: She did not choose the easiest career.

California’s supplemental nutrition assistance program. The support portal for the largest unemployment claims office in the country. New Jersey’s Department of Labor. The procurement process in the Department of Defense. Where most of us aim to spend as little time as possible, Pahlka has aimed to spend as much time as she can. “How,” she wonders, “did we get to 212 questions required to apply for food assistance?” “Why,” she ponders, “are we still using a clunky Enterprise Service Bus to manage some of the most sophisticated satellite instruments in the world?” “Why can’t we,” she asks, again and again, “make government interfaces make sense to humans?”

The answers to these queries are neatly summarized in Pahlka’s generous assessment: “When systems or organizations do not work the way you think they should, it is not because the people inside them are stupid or evil. It is because they are operating according to structures and incentives that aren’t obvious from the outside.” In such a system, Pahlka argues with compelling empathy, it’s not that the architects of the process or those managing last-mile delivery don’t want to be user-centered systems thinkers. It’s that the indulgences and necessities of the government milieu—the multitude of requirements that accrue across stakeholders and regulations, the competing interests, workarounds, bolt-ons, and power struggles—render it rarely possible.

But not totally impossible. Pahlka’s title may lead with failure, but her pages are populated by the often-dashed but never-daunted backstage heroes who keep working to make government delivery better than it was, if infrequently as good as it could be. The stories deliver the unexpected: In a book positioned as an analysis of process and policy thickets, it’s the humans that cut through, bloodied but unbeaten, with lessons that can inform a better way of making government processes work for the humans they’re meant to serve.

The locus of Pahlka’s attention may be the gap between policy and implementation, a space filled by exasperating and staggering inefficiencies and waste. Still, her premier solution set doesn’t include the typical levers of politics: money, regulation, oversight. The solution is people. “The problem underlying our delivery failures,” she writes, “is the lack of skilled technologists within government who are empowered to make the necessary decisions.” Pahlka proves an effective recruiter, and one can only hope her call to service is heard through the din of start-up clusters. The shortcomings of government service delivery are felt everywhere, each contributing to our frightening faithlessness to the government’s first promise: to be an instrument of good.