The powerful new gene-editing technology known as CRISPR is transforming biology more rapidly than any other recent technology. Yet the technology raises serious considerations to ensure that it is deployed for public benefit, according to a roundtable discussion at this week’s CRISPRcon meeting in Boston.

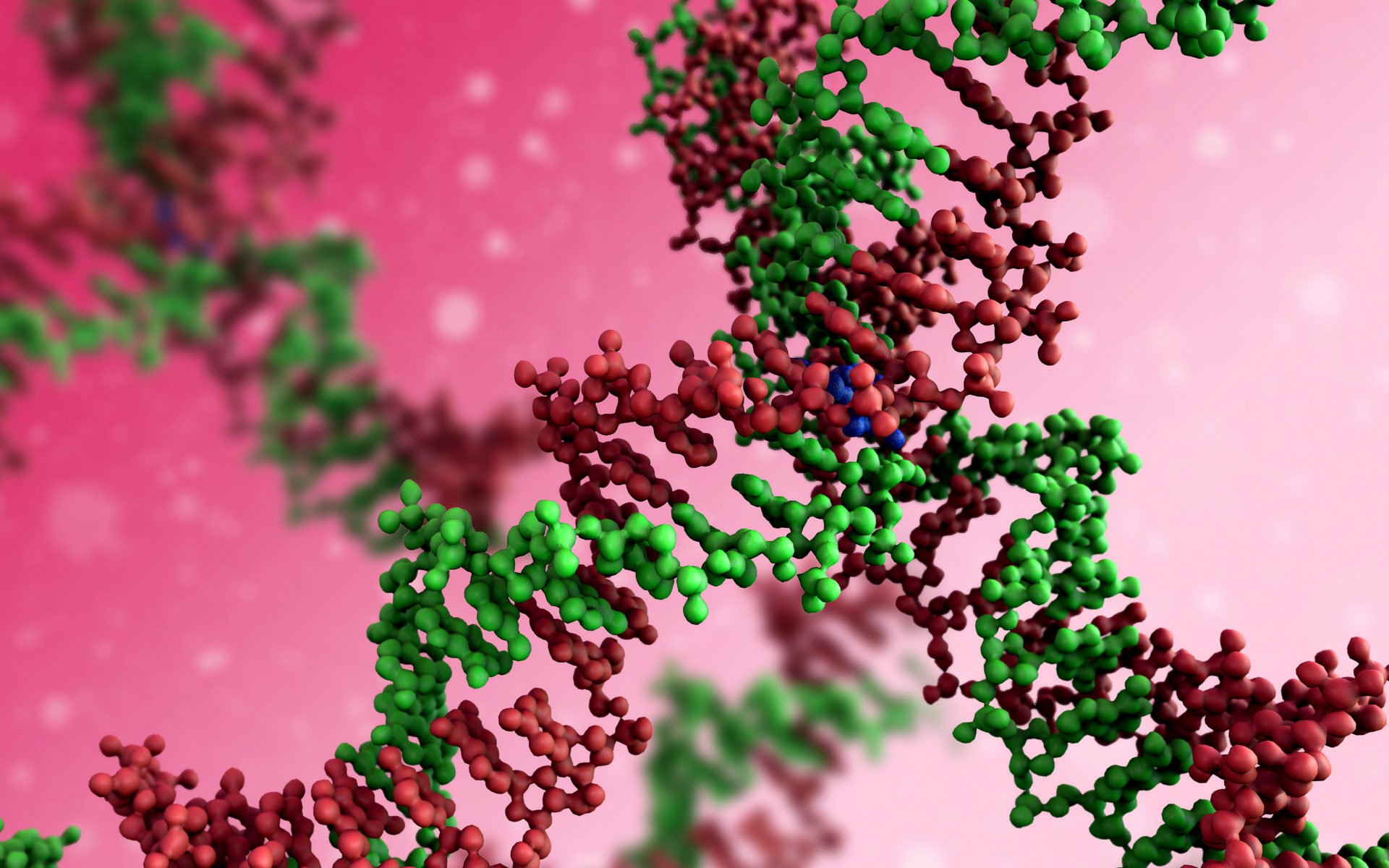

In a session focused on expanding access to these gene-editing techniques, stakeholders from a range of backgrounds reported that community values, education levels, medical and agriculture needs, and even the geopolitical climate are important factors to consider. CRISPR allows scientists to edit DNA with exquisite precision and has potential for curing disease, improving agriculture, eradicating mosquito-borne illnesses like Zika virus and malaria, and much more.

Lessons learned from the hostile reception to GMO foods can inform how scientists introduce CRISPR to the broader public, said Natalie DiNicola of Benson Hill Biosystems. Even the best intentions to educate people about CRISPR, she said, miss a fundamental point: that in these early days, all communications should be two-way. Anyone offering information about CRISPR also should be actively listening to how it’s being received, how it fits into (or breaks with) community values, and what concerns it triggers. Benefits that gene editing could offer — such as making plants more nutritious or tolerant of heat — must be balanced with benefits for farmers and society in general, she added.

Panelists also cited the importance of helping countries beyond the U.S. expand their infrastructure and experimental capacity for citizens and scientists in those nations. Ellen Jorgensen, founder of the nonprofit Biotech Without Borders, noted that this will only be possible where there are stable governments with consistent science funding. That said, it will be important to expand access to CRISPR tools not only across countries, but also beyond the major institutions currently focused on it to avoid a concentration of power, she said.

The geopolitical climate was another thread woven throughout the conversation. Scientists tend to have altruistic views of how technology will be used, said Luisel Ricks-Santi of the Hampton University Cancer Research Center, but the research community must pay attention to the political and social climate. The global rise of nationalism, added Antonio Cosme of Southwest Grows, should spark real concern over interest in CRISPR as a possible means of reviving the eugenics movement and targeting already vulnerable populations.

Despite this, there was still a push from panelists to find ways to expand access to, and interest in, CRISPR technology. Jorgensen suggested adding genetic engineering experiments to high school biology classes to help demystify the concept. Working with community “gatekeepers” could also allow for greater personalization of education efforts, added Ricks-Santi, suggesting that tying the CRISPR message into conversations that already resonate with a community could help make people more open to learning about it.

While the discussion made clear the enthusiasm for what CRISPR-powered innovation could offer society, it also highlighted the extent to which scientists and other stakeholders are grappling with potential negative or unintended consequences from a still-nascent technology.

CRISPR Community Wrestles With Potential and Peril of Gene Editing

Scientists, academics and other stakeholders gathering in Boston lauded the potential of what CRISPR-powered innovation could offer society — and grappled with potential negative or unintended consequences from the still-nascent technology.