This story originally appeared in Worth.

Just to the right of the lobby of the brand-spanking-new Shinola Hotel in downtown Detroit, there’s a casual, inviting space called the Living Room. Filled with long couches and comfortable chairs and coffee tables thoughtfully curated with coffee-table books, the Living Room does, in fact, look like a living room, albeit a large and trendy one. Visitors, most of whom are tapping away on their laptops—the rooms at the Shinola don’t have desks, so you have to work somewhere—can order food from waitresses who look exactly like the guests. A “truffle dog” costs $17, an absinthe-and-champagne cocktail called “Death in the Afternoon,” $24. Young, fit, well-coiffed, ethnically diverse, most of the laptop-tappers look like they jetted in from the Faena in South Beach or the Ace in New York. This is not what a newcomer to Detroit might expect—or, for that matter, a longtime resident. The Shinola seems to have taken everyone by surprise.

Just six years ago, hammered by decades of racial conflict and white flight, then a distressed automotive industry and the financial crisis, Detroit filed for bankruptcy—the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in American history. The city owed an estimated $18 billion to $20 billion that it couldn’t pay. You would never guess it to look at either the inside of the Shinola, handsomely appointed in leather and wood that invoke the Americana aesthetic of the Detroit-based watch company, or the outside. For one thing, the Shinola’s location is a statement; it’s at the intersection of Grand River and Woodward Avenue, an iconic street for Detroit and the first paved road in the country. There’s been a lot of history here—and a lot of change. For many years the Shinola building had housed a Rayl’s department store, then a jewelry store, then a wig shop. Now the nearby stores include Warby Parker, Lululemon, John Varvatos and, naturally, Shinola, one of whose seductive ateliers is attached to the hotel.

Across the street there’s a massive hole in the ground known as the Hudson’s site. It was once the location of the flagship Hudson department store, a local institution that closed in 1983. Coming soon? A 912-foot-high, mixed-use office building, the tallest building in the state. And finally, just past that is the Compuware building where about a decade ago Dan Gilbert, the billionaire founder of Quicken Loans, moved some 1,700 of his employees in from suburban office parks—a different kind of turning point for Detroit.

“Dan was a huge catalyst [for Detroit’s turnaround], seeing the opportunity in distressed real estate where others either didn’t see the opportunity or weren’t willing to take the risk,” Shinola CEO (and former Detroit Lions president) Tom Lewand says.

“Quicken Loans, and the region, needed to stop the brain drain of educated young people leaving the state to work in cities like New York and LA,” Gilbert told me via email. “We needed to give them a reason to stay.”

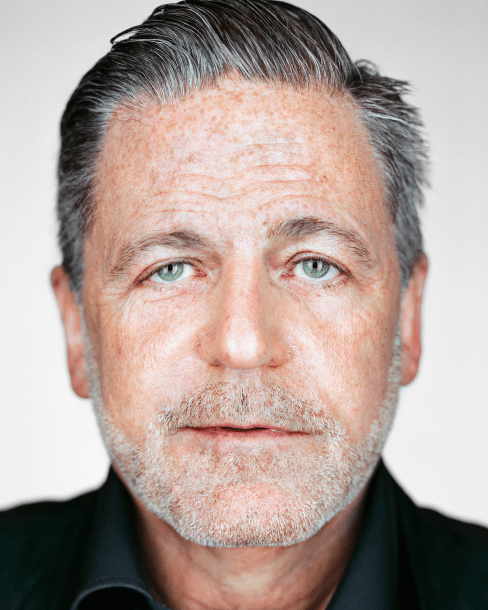

Gilbert is, in fact, the common denominator of all these Detroit pivot points. His real estate company, Bedrock Detroit, partnered with Shinola to build the hotel, which opened in January. It’s also building that skyscraper across the street. Bedrock, which now employs over 17,000 people in the city, owns over 100 buildings in downtown Detroit, an astonishing and unprecedented concentration of private ownership in the heart of an iconic American city. (Gilbert has appeared at Techonomy’s conferences in Detroit.)

Gilbert and Bedrock have attracted national attention for their investments in Detroit, and rightly so: What the billionaire entrepreneur has accomplished for the city where he was born is an incredible story. But it’s really part of a larger story: How over the past quarter century the massive rise in private wealth has allowed billionaires across the country to acquire huge chunks of land in American downtowns, literally rebuilding and reshaping the map of the country.

Over the past quarter century, the rise in private wealth has allowed billionaires to acquire huge chunks of land in American downtowns, rebuilding the map of the country.

What has happened piecemeal in our cities has, as a collective phenomenon, gone largely unnoticed by the media. And, to be sure, it takes many players to influence the course of a city—politicians, philanthropists, community activists. In Detroit, for example, folks are quick to point out that you can’t give all the credit to Gilbert, you have to talk about General Motors, the Ford family, the Ilitches of Little Caesars fame and the leadership of mayor Mike Duggan.

But the billionaires among them have an outsize influence. Their impact will endure for decades, probably centuries. For much of our lives, and for generations to come, many of us will live and work in buildings, eat in restaurants, watch sports events or concerts and gather in public places that were all imagined, created and owned by a handful of extraordinarily wealthy men.

That reality may sound concerning—so much influence over people’s lives in the hands of so few—and perhaps in the long run it should be. Maybe after a while, when we forget somewhat how bleak were the circumstances of many U.S. cities, we’ll grow resentful of such concentrated ownership and its unintended consequences. Yet here’s the truth at the moment: So far, these investors are doing a pretty good job of elevating the cities they’re buying into. Yes, there are exceptions: New York’s Hudson Yards—when the revolution starts, this place is in trouble—is probably one. But there’s ample evidence that American cities are significantly better off because of this wave of investment from the ultrarich.

Take the case of Milwaukee, Wisc. Since the end of World War II, Milwaukee has been sapped by economic decline, particularly the loss of manufacturing jobs and brewery closings. Further slammed by the Great Recession, Milwaukee suffers from crime and poverty rates well above the national averages. Still, it’s a city with history and character and heart, the kind of place you root for but not with a ton of confidence.

These investors are doing a pretty good job of elevating the cities they’re buying into.

In 2014, though, New York-based investors Wes Edens and Marc Lasry, cofounders of the private equity firms Fortress and Avenue Capital, respectively, paid $550 million for the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks. (Two other partners, hedge funder Jamie Dinan and real estate developer Mike Fascitelli, came on later.) Many sports business observers felt that the amount was out of whack for a small-market team. Two factors convinced the investors otherwise. One was the Bucks’ share of NBA television money, which was exactly the same as that of the league’s other 29 teams. The other was that, along with the team, the new ownership also acquired about 30 acres of developable downtown real estate, land that had lain dormant for decades. It’s worth repeating just to let that sink in: 30 acres of developable downtown real estate.

“We had really a blank slate,” Edens told me. “It was unprecedented, remarkable that it even existed—a hallmark of a hollowing-out of American cities over the last couple of decades.” With great land comes great responsibility. “It was up to us to get it right,” Edens says.

The results are encouraging. With a split of private and public money, the Bucks’ new owners built a $524 million arena, now called Fiserv Forum, to replace the aging Bradley Center, which had fallen behind the amenities race of modern arenas. Fiserv Forum is a great place to see what is now a great team; at 60-22, the Bucks had the league’s best regular season record this year.

Simultaneously, the development of the surrounding land is invigorating the arena’s neighborhood, extending the boundaries of Milwaukee’s downtown and giving suburbanites new reason to come back. The Bucks are building restaurants, hotels, retail, apartments, office space. “The vision here is: How do we continue to build density and evolve the neighborhood?” Bucks president Peter Feigin told Arena Digest. That mixed-use density, anchored by the arena and its surrounding plaza, will attract visitors, then businesses, tax revenue and jobs. One powerful example of the Bucks’ impact: The Democratic Party chose Milwaukee as the site of its 2020 convention. Electoral politics had something to do with that, surely. “But,” Feigin said to me, “it wouldn’t have happened without this new arena.”

It’s not that every social and economic problem has been magically fixed—far from it. “There’s still a lot of inequity [in Milwaukee], a lot of needs,” Edens acknowledges. “I’m happy with the progress that we’ve made so far, but it feels like we’re just at the beginning. I’m just a big believer that private enterprise can be a big part of the solution.”

Head south to San Antonio and you’ll see a similar phenomenon. This city of about 1.5 million people never faced circumstances quite as dire as Detroit or Milwaukee, thanks in large part to the economic buffer of 18 military bases in the area. Even so, its downtown suffered a different kind of decline.

“I’m just a big believer that private enterprise can be a big part of the solution.”

–Wes Edens, investor

One of America’s most historic and culturally diverse cities, San Antonio played host to the 1968 World’s Fair, known as HemisFair ’68. That event led to the ongoing expansion and development of San Antonio’s now famous River Walk, the scenic, twisting path through downtown that’s a tourist magnet. Other HemisFair attractions were converted to support what would prove to be an enduring convention business.

Yet even as tourists and business travelers came to San Antonio, downtown employers were departing for the city’s suburbs, part of a national exodus from challenged downtowns. “The tide went out on downtown employment,” says David Adelman, the founder of Area Real Estate and one of the most prominent developers in the city. Downtown San Antonio was filled with visitors, but nobody lived there. That started to change in the early 2000s, thanks in significant part to mayors Phil Hardberger and Julián Castro, both of whom made housing a priority. But perhaps the most dramatic breakthroughs resulted from the efforts of two billionaires, Christopher “Kit” Goldsbury, who made his fortune building the salsa maker Pace Foods and selling it to Campbell Soup for $1.2 billion in 1994, and Graham Weston, who became a billionaire by investing in the web server company Rackspace, which is headquartered in San Antonio.

Over a period of almost two decades, Goldsbury dreamed, planned and built Pearl, an entire neighborhood that, like Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee, has extended the boundaries of its city’s downtown. Its centerpiece is the dramatic and outstanding Hotel Emma, a spare-no-expense conversion of a defunct brewery. But Pearl also features housing, restaurants, local retail—there’s an actual indie bookstore—an outpost of the Culinary Institute of America, a farmers market and other community-minded elements. It’s attracting visitors from the San Antonio suburbs and around the country who would never have dreamed of coming to the area until, after decades of work, Goldsbury’s creation became an overnight success.

Unlike Goldsbury, Weston and his partner in real estate, a Rackspace veteran named Randy Smith, have no master plan. Through their company, Weston Urban, they’ve simply been buying and developing as much real estate in and around San Antonio’s central business district as they can, given cost and market conditions. “There’s no playbook for what we’re doing,” Smith says. Their mantra is to address a debilitating problem: San Antonio’s young people frequently leave town for Austin, Dallas, Houston and the coasts. “Our goal is to help build the city that our kids will want to move back to,” Smith says.

Probably their biggest project is the about-to-open Frost Tower, a 24-story gleaming office building with ground-floor retail. The building looks substantial, heavyweight, like something you might see in Chicago or LA. It’s the first skyscraper built in San Antonio since 1988, and Smith says it’s already having an impact on the way San Antonians think about their city. “When people see it, they’re like, ‘Downtown’s open for business.’ It’s this great, beautiful, shimmering reminder that San Antonio should believe in itself.” Since construction began, six other office projects have been announced, with three having broken ground.

A few weeks ago, Smith brought a visitor to the Frost Tower’s unfinished top floor, which offers an impressive 360-degree view of the San Antonio skyline, and commenced a finger-pointing tour of Weston Urban properties. Smith started with the first building that then 27-year-old Graham Weston bought, now called Weston Centre. Then the Milam, the first air-conditioned high-rise in the country. A parking lot next to it. An eight-story red brick building, the Rand. A 140-year-old hotel. Another parking lot. An 11-story white limestone beauty. A hoped-for acquisition, the Hotel Robert E. Lee, a century-old converted apartment building. (“Step one, change the name,” Smith says.) The list goes on…and on…and on. Many of the buildings are stunning examples of early-20th-century urban architecture. “Detroit and Cleveland have building stock that we would die for,” Smith says. “We have building stock that Austin, Dallas and Houston would die for.”

Smith’s enthusiasm is infectious, as is that of most of the people involved in these urban redevelopment projects. It’s bolstered by the fact that many of the people involved grew up in the cities they’re rebuilding; they’re motivated by profit, yes, but passion for their hometown is also powerful. And they seem to have learned from the past—not just about the urgent nature of historic preservation, or the centrality of multi-use spaces in creating livable environments, but about also the fact that there can be no sustainable economic growth without racial and economic justice. When moving Quicken downtown, Dan Gilbert says, “We quickly realized the need for top talent to grow a business, and our investment in Detroit has helped to pave the foundation for not only our company, but the city to grow. We established a ‘for more than profit’ ideology throughout our family of companies that keeps people and communities first, not profits.” In Milwaukee, the Bucks ownership says much the same, as do the San Antonio developers.

If these new powerbrokers mean what they say about inclusion, and if their approaches work, what they’re doing could underpin a meaningful transformation of the future of American cities, one in which shiny new buildings and hipster coffee shops bring with them a rising tide of economic growth. As Shinola CEO Tom Lewand puts it, “My own belief is that economic solutions help create the social solutions. Having that conversation is easier when the economic landscape is fairer.”