Drought. Famine. Turbocharged typhoons. These are all looming dangers we’ve learned to fear from climate change. But according to one public health expert, perhaps the greatest threat of all will come from the often-overlooked fungal kingdom.

There are more than 6 million species of fungi on our planet, but just a handful of them are known to be pathogenic to humans. As Arturo Casadevall from Johns Hopkins University noted in a presentation at the recent meeting of the Association for Molecular Pathology, we tend to take little notice of these organisms even when they do infect us — typically with conditions as trivial as athlete’s foot. But if Casadevall’s scientific investigations are on the right track, fungi might very well represent an imminent health threat. And that’s being triggered by climate change.

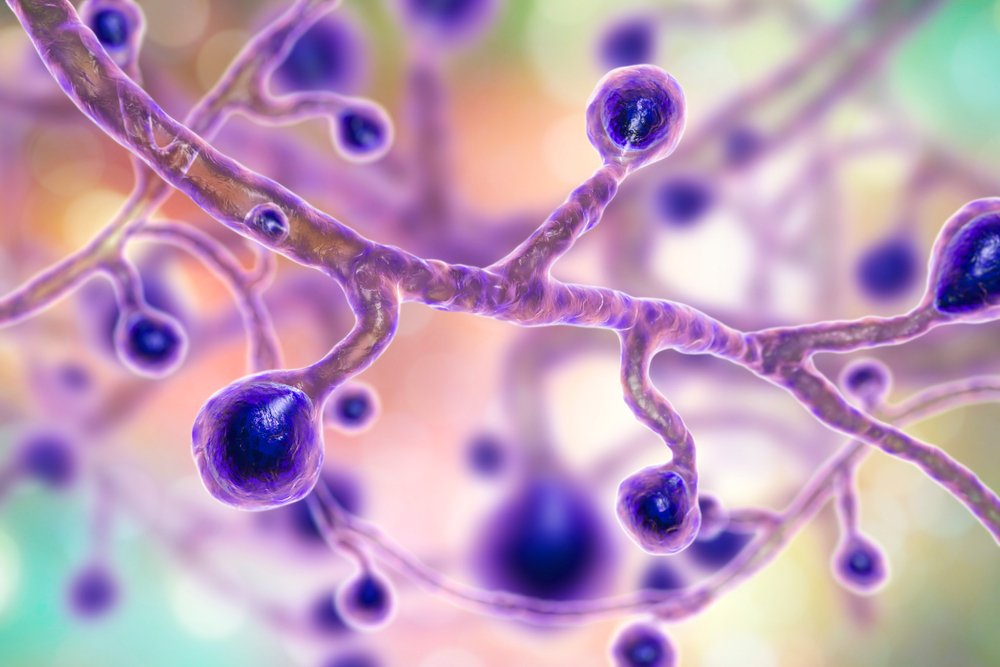

For organisms that aren’t mammals, fungi are already the source of often-lethal infectious disease. Everything from bees to trees can fall victim to fungal species, which have evolved a vast array of virulence factors to make them highly effective at evading a host’s immune system.

What keeps us and our fellow mammals safe is our uniquely high body temperature. Indeed, Casadevall credits the post-dinosaur mammalian population boom to fungi, which killed off or at least weakened many natural predators. Because fungi struggle to survive in the sustained heat of a mammal host, these animals had an evolutionary advantage. But mammals are by no means immune to fungi. Bats, for instance, are mammals that undergo major temperature swings. In the summer, their body temperatures are about the same as ours; but in the winter, their temperatures plummet. Scientists have found that summer-warm bats are resistant to the deadly fungus responsible for white-nose syndrome, but their cold winter bodies provide ready hosts for that fungus.

But, like all organisms, fungi can adapt. And as the earth’s temperature rises, fungal species that were previously unable to tolerate mammalian warmth are becoming more acclimated to it. According to Casadevall, we’re already seeing the earliest public health consequences of this. Candida auris is a type of yeast that has rapidly become a scary source of infection — one that is often resistant to many or all anti-fungus treatments on the market. According to Casadevall, this fungus wasn’t documented in medicine prior to 2007. At that time, it emerged independently in three separate places, all with hot climates: India, Venezuela, and South Africa. The earliest infections were found in cooler body parts, like ears. But now, Casadevall says, Candida auris is much more adapted to heat and can easily withstand temperatures several degrees higher than the human body.

As Casadevall sees it, the fungal kingdom already has everything it needs to be dangerously infectious. If these species begin to adapt heat tolerance too, then all mammals — including us — will become easy targets for deadly pathogens. We are a population ripe for the picking.

But Casadevall believes we can fight back. To prepare for what appears to be an inevitable development in infectious disease, he recommends a four-pronged approach. First, we must increase surveillance of new fungus-based diseases in plants and animals to detect imminent threats. Second, we should boost research into host-pathogen interactions in species beyond our own to understand how other systems deal with infection. Third, Casadevall calls for development of new antimicrobial strategies, with a wider scope than just creating new drugs. Finally, scientists should develop threat matrices to stratify new pathogens and outbreaks; this would guide treatment and epidemiological response. Taken together, he says, these approaches could help experts predict the health risks associated with each species that breaks through our natural body-heat defenses.