More than 60,000 babies are born in the US each year from in vitro fertilization procedures. But when the procedures were first developed back in the late ’70s, people referred to these children as “test tube babies.” The process sounded like something from a sci-fi novel and was greeted by many with fear and disgust.

We’re seeing a similar phenomenon today with the latest advance in reproductive science, a process involving mitochondrial replacement that has been given the cringe-worthy label “three-parent babies.”

“There’s a ‘yuck’ response,” says Dr. Robert Klitzman, director of the bioethics masters program at Columbia University. But that “doesn’t reflect a careful thinking out of the issues,” he continues. The first baby created from this new technique was born earlier this year and just announced publicly.

Understanding those issues, and the process itself, involves a quick dip back to high school biology. When we think of the human genome, we’re referring to the DNA housed in the nucleus of each cell. It contains more than 20,000 genes and exists on 23 pairs of chromosomes. The DNA sequence we have today was formed by millions of years of evolution in which we lost genes, altered genes, and even acquired new genes from organisms like bacteria. Then there’s the mitochondrial genome, a separate set of DNA that lives outside the nucleus and contains just 37 genes. Scientists believe the mitochondrial genome is essentially the remains of bacteria that got swept up in the cell during evolution, but never integrated with the DNA inside the nucleus.

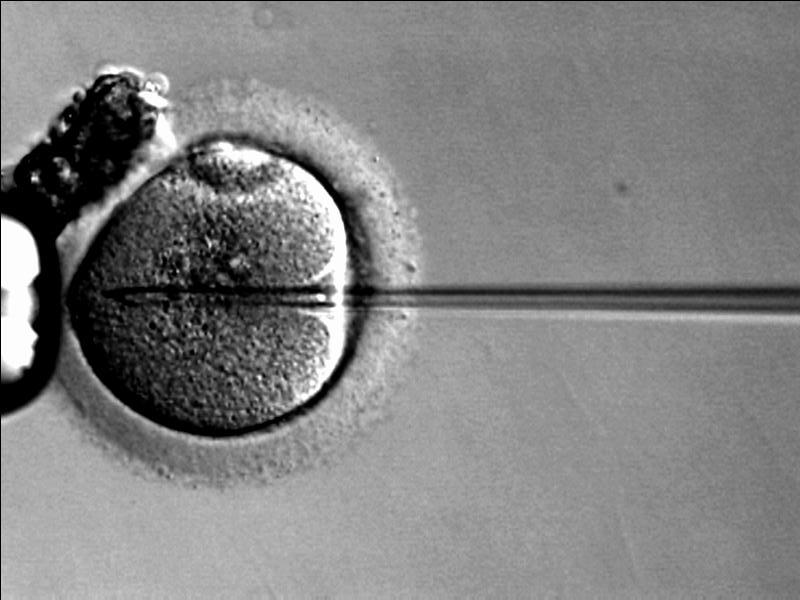

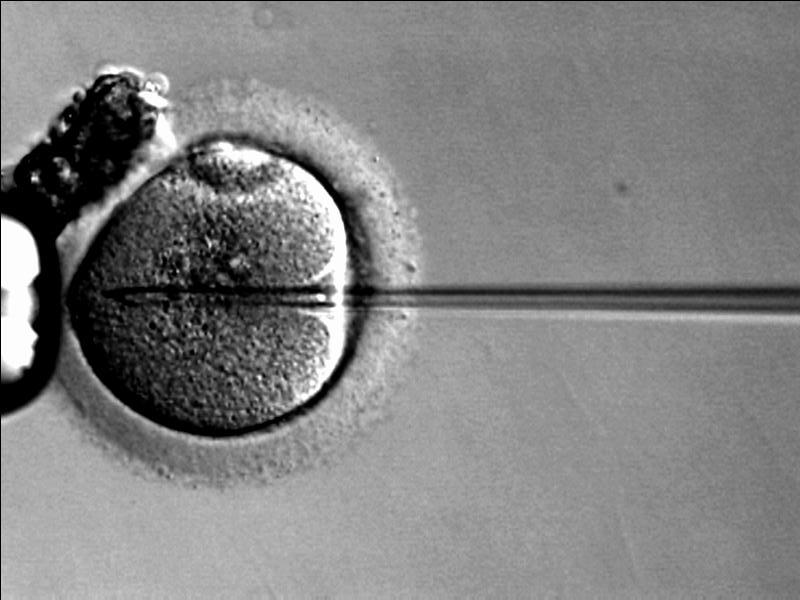

Even though mitochondrial DNA is separate, it still contributes to human disease; women with faulty mitochondrial genomes pass them on to their kids. For the past few decades, researchers have sought ways to let these women have healthy children—passing on their human genome without passing on their mitochondrial one. What if they could create an embryo with the mother’s and father’s DNA, adding in just the mitochondrial DNA from a healthy donor?

This has been accomplished in different ways over the years, with the first such children born 20 years ago. Concerns about those early procedures, which involved destroying an embryo to create another one, in addition to some negative outcomes early on, led to bans on this kind of research in the U.S. and elsewhere. This latest advance, however, does not create an extra embryo and was just approved in the U.K.

For the baby just born, fertility specialists used the mother’s egg, father’s sperm, and a healthy donor’s mitochondrial DNA in an otherwise typical IVF process. Because of the different national regulations governing this procedure, the work was done in Mexico by New York scientists for a Jordanian couple who had previously lost children to deadly mitochondrial diseases.

Klitzman likens the process to an organ transplant where something specific and diseased is swapped out for something healthy. “If I had a kidney transplant, I wouldn’t say I was created from three different people,” he says, calling the “three-parent” label a distortion of the science.

That said, he doesn’t think the label is the only thing that deserves consideration. There are real ethical issues, and there has been no clear accounting for benefits and risks, or of the rights of everyone involved. The process also involves changing a child’s genes, albeit in an incredibly targeted manner, and that alone merits discussion. “My sense is that the potential benefits outweigh the risks,” Klitzman says. “I would argue that as long as the risks are clearly explained to a potential parent, that they should be able to make the decision themselves.”

While many more studies will have to be done to ensure the safety and effectiveness of this procedure, it’s hard to find fault with an approach that lets parents conceive healthy children when they otherwise could not—even if that approach makes some people squeamish. Ultimately, babies born through this procedure may be seen like any other IVF baby, and the process could become as widely accepted as using donor eggs or sperm to overcome other reproductive obstacles.

Meredith Salisbury is Techonomy’s correspondent for genomics and genetic health, and will moderate a session at Techonomy 2016 on Nov. 10 entitled Genetically-Modified Everything. Dr. Robert Klitzman, quoted above, will also be at the conference and participating in a preceding set of sessions called Techonomy Health.

The Three-Parent Baby Is Not as Weird as You Think

People may have a "yuck response" when they hear about this new experimental technique for creating healthy babies. But it isn't as huge a leap from what we're used to as most reports would suggest, as Techonomy's genomics expert explains. Like a top medical source she quotes here, Salisbury will be continuing this conversation at Techonomy 2016 on November 10.