This piece originally appeared in FIN, James Ledbetter’s fintech newsletter.

While there are probably few superior alternatives, a Congressional hearing is typically a poor venue for gaining insight into the American financial regulatory system. Even when the events are not contentious, they can seem like experiments to concoct a maximum number of ways for people to talk past one another. Not only are answers infrequently in direct response to the questions posed, there is a kind of competition to formulate questions that *can’t* be answered, usually because they are asked in bad faith.

That sorry dynamic was on full display this week as Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) chair Gary Gensler testified before the Senate’s committee on banking, housing and urban affairs. A striking amount of time was spent discussing cryptocurrency, which is a little strange, given all the other issues at hand—such as mandating that public companies disclose their climate risks—and given that the same committee devoted an entire hearing to cryptocurrency as recently as July. It appears that the fury created by proposing a cryptocurrency tax as part of the infrastructure put the issue on several Senators’ agendas.

Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA) honed in on an issue FIN has covered regularly: are cryptocurrencies securities, from a regulatory standpoint?

I’m frustrated by the lack of helpful SEC public guidance explaining how you make this distinction—what makes some of them securities while others are not securities?….Why wait to make the SEC’s views known only when it swoops in with an enforcement action, in some cases years after the product was launched? This is regulation by enforcement, and it’s very objectionable.

These are, superficially, legitimate questions, even if Toomey had to know that Gensler was not going to answer them in any greater detail than he or the agency have many times before. “There is a small number that aren’t” securities, Gensler said—presumably referring to the Bitcoin and Ethereum exceptions the SEC articulated in 2018—“but as [previous SEC] chair [Jay] Clayton said when he was in front of Congress, I think very many of these facts and circumstances are investment contracts.”

This points to a reality that doesn’t fit into the hearing’s theatrical requirements. Although the SEC has very broad authority granted by Congress, it’s a fairly small agency with limited staff. There are an estimated 6500 cryptocurrencies in existence, with new ones being created every day. It is simply not possible for the SEC or anyone to examine the conditions of every existing crypto coin, much less apply the appropriate tests to determine whether or not they are securities. To lay down universally applicable rules is practically a guarantee of obsolescence, given how fast the space evolves. The SEC has tried, through actions like the charges against Ripple, to send the signal that many such coins are securities—and for that it gets damned by Toomey as “very objectionable.”

At another point, Toomey hit on another favorite FIN topic. “To me, a stablecoin doesn’t meet the second prong of the Howey test, that there has to be an expectation of profit from the investment,” Toomey said. This concern-trolling seems at a minimum a little late; FIN dealt with this prong of the Comey test applied to stablecoins in our 7/25 installment:

This could be the trickiest of the four tests. It’s entirely conceivable that a purchaser of a USD-backed stablecoin would say “I did not buy this coin because I expected, or even wanted, to make a profit. I bought it as a store of value,” or “I bought it because it was a seamless, low-fee way to move my money from Bitcoin to Ethereum without having to convert back into fiat currency.” Those arguments are logical but essentially untested in this context. The case law here seems to hinge on how the investment is pitched to the investor….A flock of lawyers is going to make tons of money arguing over this.

Toomey asserted to Gensler: “Stablecoins do not have an inherent expectation of profit, they’re just linked to the dollar….Is it your view that stablecoins themselves can be securities?” Unsurprisingly, Gensler responded: “I think, Senator, they may well be securities,” reminding his audience that “the laws that we have right now have a very broad definition of security.”

Toomey’s grandstanding reflects a too-common stance in and around the crypto community that Gensler is hostile to cryptocurrency and blockchain technology. “I’m not negative or a minimalist against crypto,” Gensler said, somewhere between befuddled and perturbed. Reviewing the Senate hearing, a Coindesk podcaster, citing a tweet, said “[S]ome astute observers noted…Gensler’s use of a term that literally has never been used before: “stable value coins” in place of “stablecoins’.” The implication of outrage seems to be that this phrasing is supposed to justify SEC regulation of stablecoins by way of its oversight of stable value funds.

But, er, no: Gensler used this exact term in his August remarks to the Aspen Security Forum. It’s silly to pretend that Gensler is engaged in some kind of linguistic drip-by-drip plan to crack down on stablecoins. Financial regulators have been warning about the systemic dangers of stablecoin growth for months, and this week the Treasury Department got in on the act. At some point the industry and its supporters are going to have to live with a truth that Gensler, in his low-key way, tried to articulate: wanting to regulate a financial product or company does not mean that you oppose its existence.

Why Trust Matters

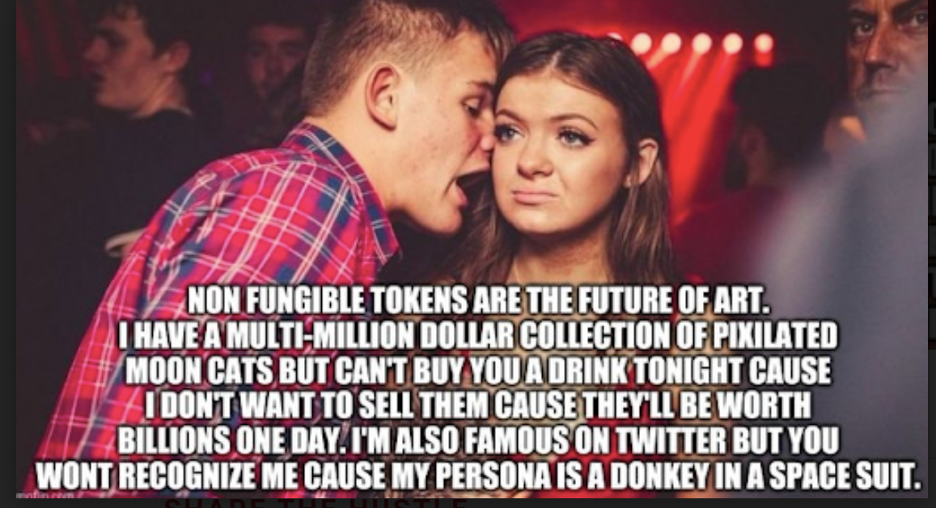

As a general practice, FIN does not cover the world of NFTs very much, but this week’s developments at OpenSea, the largest NFT exchange, make an important point with potentially far-reaching consequences. An anonymous Twitter account began posting accusations that Nate Chastain, head of product at OpenSea, used secret Ethereum wallets to purchase NFTs before they were promoted on the OpenSea home page. This is akin to what in the stock market is called “front-running,” a time-honored practice that is usually banned. On Wednesday, OpenSea published a blog post, admitting that the story was true and saying that it had asked for and received Chastain’s resignation: “We have a strong obligation to this community to move it forward responsibly and diligently.” Remarkably, as Frank Chaparro of The Block points out, what Chastain did is probably not technically illegal—precisely because OpenSea is not a registered exchange and NFTs are not regulated as securities. This is exactly the point that Gensler was trying to make to the Senate; if you have innovation for too long outside the regulatory framework, consumers will get burned and trust in the technology will erode.

This piece originally appeared in FIN, James Ledbetter’s fintech newsletter. Ledbetter is Chief Content Officer of Clarim Media, which owns Techonomy.