Most of us had never heard of mRNA vaccines before they burst onto the stage to rescue us from the COVID-19 pandemic. They represent a huge leap forward in how pharmaceutical scientists can design vaccines or even new disease treatments — and they may also turn out to be the right approach for tackling infectious diseases for which no previous vaccine technology has worked.

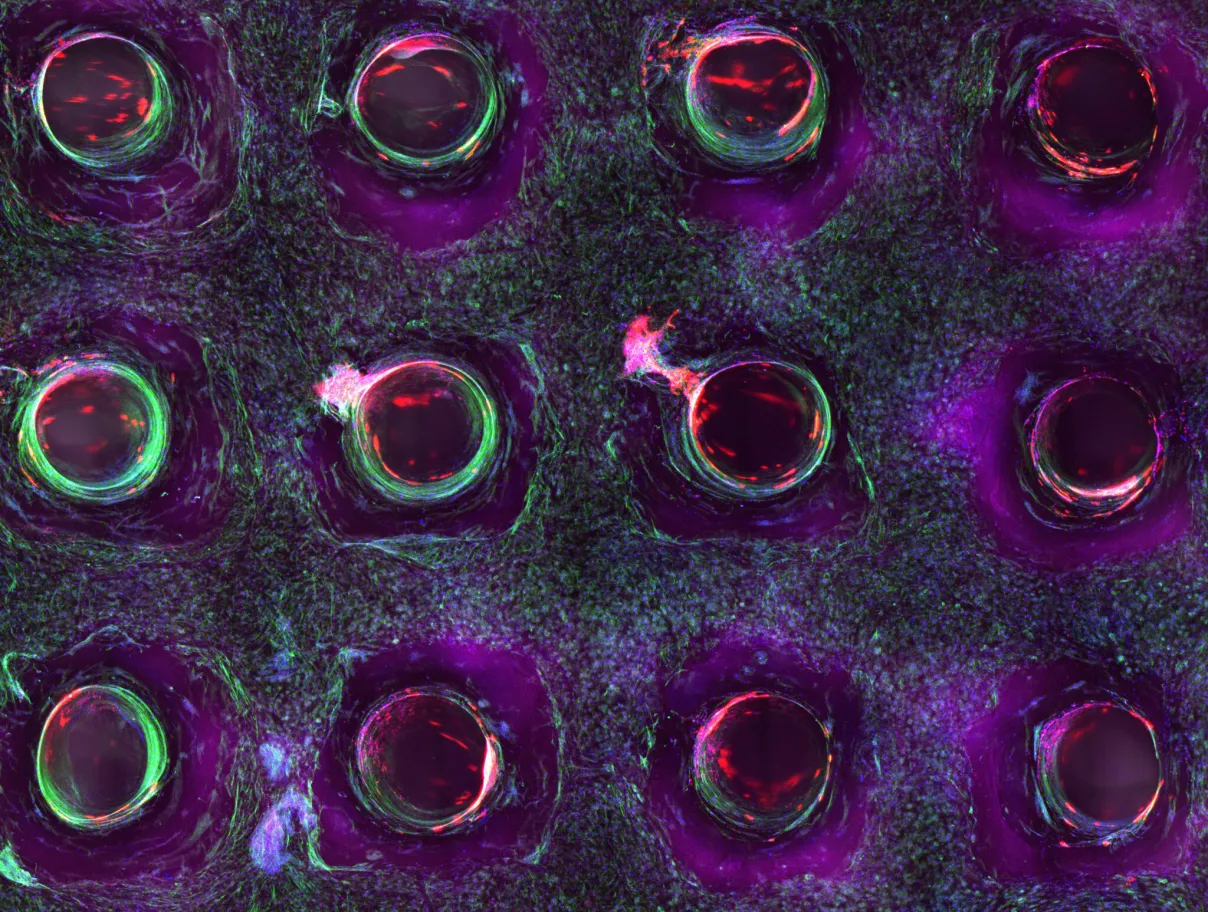

One of the reasons mRNA vaccines are so exciting is their inherent flexibility. They work by providing specific genetic instructions that allow the body to produce a tiny piece of the pathogen they aim to protect us from. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus responsible for COVID-19), the vaccine prompts our own cells to manufacture just the viral spike protein found on the exterior of the virus. Our bodies never have to be exposed to the real pathogen, but the little protein our cells churn out is able to teach our immune system how to recognize the real thing, and build a defense against it. Should we then come in contact with the pathogen, our immune system is primed and ready to respond.

The flexibility is built right in to this technology. mRNA vaccines are able to tell your body to make whatever’s needed to combat a given disease. Vaccine developers just need to plug in the right genetic instructions, and in theory these vaccines could protect against anything.

The reality, of course, is not so simple. Each new vaccine candidate will require careful development and testing before it can be considered for use in humans.

mRNA vaccine technology has been under development in labs for years, and it’s no coincidence that this approach was so important for COVID-19. After two earlier coronavirus outbreaks (SARS in 2002 and MERS in 2012), scientists began intensively studying whether mRNA vaccines could be useful against this family of pathogens. “The science that fueled the COVID-19 vaccine has been … happening for at least 10 years,” said Kizzmekia Corbett, a research fellow at the NIH Vaccine Research Center whose work contributed to the Moderna vaccine, in a recent virtual address sponsored by Carroll Community College in Maryland. (Corbett is moving shortly to the Harvard School of Public Health.)

Because that research came to fruition so successfully during the pandemic, interest in creating new mRNA vaccines is rising to a frenzy. There’s a long list of other uses. At Moderna, for instance, other candidates in clinical testing include vaccines for cytomegalovirus, Zika, Chikungunya, and influenza, among others. BioNTech, the company that partnered with Pfizer to create the other COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, is in the early development phases of vaccines for HIV, tuberculosis, and influenza.

Scientists also hope that mRNA vaccines can be engineered to provide universal protection against entire families of viruses. Already, researchers are working toward a pan-coronavirus vaccine that would protect against current and future pathogens from this family of viruses. “I’m hoping within a year we have pan-coronavirus vaccines,” said Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, at Techonomy’s recent Health and Wealth of America event. “Instead of doing this variant-by-variant thing, we would just knock them out.” If effective, such protection could potentially be sufficient to prevent future coronavirus pandemics.

Or imagine a pan-flu vaccine that would protect against all strains of influenza, eliminating the need for the annual flu shot. If scientists could find a piece of the virus that stays the same across all strains, that snippet might be the basis for an mRNA vaccine providing broad protection.

Topol believes coronaviruses are the ideal starting place for this kind of vaccine approach. “This, fortunately, is a family of viruses that is so ideally suited — and if we can do it for this family, then we should be good to do it for others,” he said.

mRNA technology is also being developed for applications beyond conventional sorts of vaccines, including to combat diseases after their onset. There are now mRNA-based cancer vaccines in clinical trials, for example. Unlike the HPV vaccine designed to prevent cancer, such mRNA vaccines would be used to treat patients diagnosed with cancer.

Corbett sees unlimited potential for mRNA-based interventions. “It can go anywhere. That’s the beauty of science: all things are possible,” she said. Ultimately, the NIH researcher predicts there will be a “complete transformation of medicine because of messenger RNA.”