There are so many acronyms to know these days, and DAF—for donor-advised fund—is not at the top of the list for most people. But these personal or family philanthropies are coming under growing criticism for a few reasons. Unlike foundations, which have to give away 5% of their net asset value annually, DAFs can sit on their money indefinitely. Yet donors get immediate tax benefits, regardless.

Today, two organizations that admit to very different philosophies around philanthropy released a joint survey that they say shows public disapproval of how DAFs operate. Describing themselves as an “odd couple,” progressive Inequality.org and conservative publication The Giving Review collaborated on a survey of 1,005 American adults conducted on February 15 and 16. (It’s a follow-on from a similar 2022 survey done by Inequality.org.)

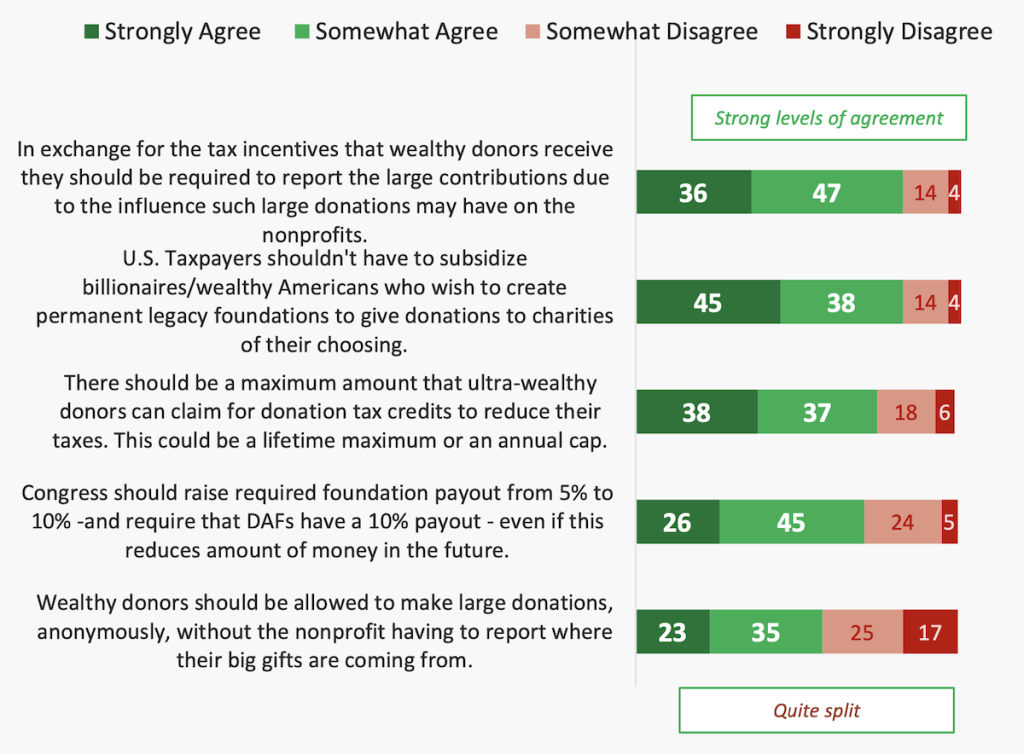

According to the report, majorities of people—whether they identified as “left,” “middle,” or “right”—agreed (either “strongly” or “somewhat”) on several philosophical points. For instance, U.S. taxpayers shouldn’t subsidize wealthy Americans who create self-perpetuating charitable funds. There should be a limit on how much donors can claim for tax credits. And Congress should impose annual payout requirements for DAFs.

What’s a DAF?

But there was also wide agreement on another point: Most people don’t know what a DAF is or how it works. Only 17% said that they are aware of DAFs. And only 35% knew that wealthy donors could get tax breaks of up to 74 cents on the dollar.

“The reality is, most people do not understand them,” says Chuck Collins, director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at Inequality.org. “What this poll does is…we explain how some of these things work and then ask, ‘What do you think of this?'”

The gist of a donor-advised fund is that it provides a nonprofit vehicle for a wealthy individual, couple, or family to set aside tax-deductible money—and have more input on grantmaking than through a traditional charitable foundation. One big benefit is that the donor can claim the tax deduction the year they put money into the DAF, regardless how long it takes to get that money out to good causes. Another is that they can roll a wide array of “non-cash assets” into a DAF to get that tax deduction, such as appreciated stock (to reduce capital gains taxes) or cryptocurrencies.

No Spending Requirements

DAF donors can decide when and how much to parcel out. That’s a key sticking point for reformers like Collins and for some legislators looking to make changes. Once they know about it, the public doesn’t like the practice, either, according to the study. Fifty-four percent of survey takers said that DAFs should pay out funds in just two years. And 25% said it should be within five years. Just 18% chose the option, “Take as long as [you] want,” which is the status quo under current law.

“What was fascinating is, most of the reform proposals for DAFs are like, you should have a payout in 15 years,” says Collins. “The public opinion is like, you should have a payout in five years, [or] you should pay it within two years.”

The most prominent of those proposals are in bipartisan Senate and House bills for the Accelerate Charitable Efforts Act. ACE, as it’s called, would push DAFs towards a 15-year payout. (The legislation has been introduced a few times in recent years but hasn’t gotten far.)

Regardless how long a DAF lasts, the survey indicates that people would like some yearly payout requirements, too. Most agreed (strongly or somewhat) that Congress should require DAFs to direct 10% of their assets to charities annually (and that the current 5% requirement for foundations should also go to 10%). The ACE Act would require that DAFs pay out at least 5% a year.

Cutting Back Tax Benefits

The demand for quick payout is justified, says Collins, because DAF owners are getting tax breaks—what the survey calls a subsidy for “billionaires and other wealthy Americans.”

“I think it reflects that sense that this is a value proposition here,” he says. “You get a tax break. And you do your part of the deal, which is to give it to the Boys and Girls Club, give it to the food bank, give it to somebody other than your charitable organization that you control.”

The ACEs act would create a financial incentive for this by awarding tax breaks, not when donations go into the DAF, but only when the funds go out to charities.

In addition, most survey takers somewhat or strongly agreed that there should be a cap on how much money donors can receive tax credits on—either per year or over their lifetime. About half of those favoring a lifetime cap would put it at $100 million. Others went higher—up to $1 billion.

Tax benefits also played into the question of whether donors should be able to make anonymous gifts. When asked that basic question, 58% said that recipients should not have to disclose their benefactors.

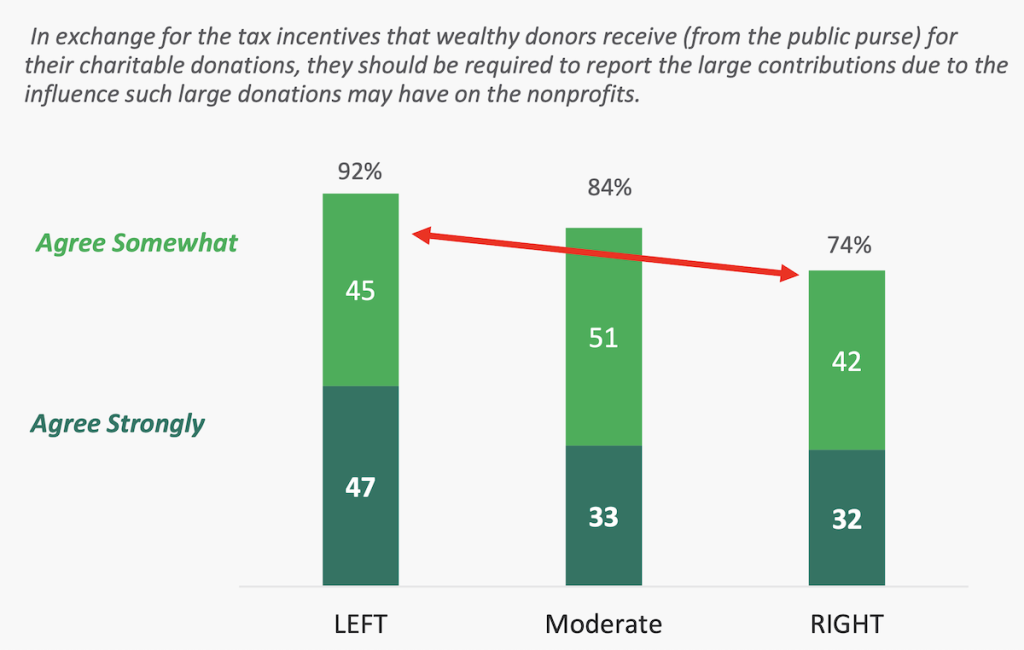

But the answers changed dramatically with another question that pointed out two things. These gifts are subsidized through tax breaks, and they could be given out to exert influence over the nonprofits. Here the numbers more than flip, with 83% overall favoring disclosure—spanning majorities from 74% among the right all the way to 92% on the left.

“If you give your money away, and you didn’t ask for a tax deduction, I don’t care what you do,” says Collins. “But if you want the rest of us to essentially subsidize your gift by reducing your taxes, then there’s a public interest in knowing what you did with the money and a public interested in wanting you to fulfill the promise.”