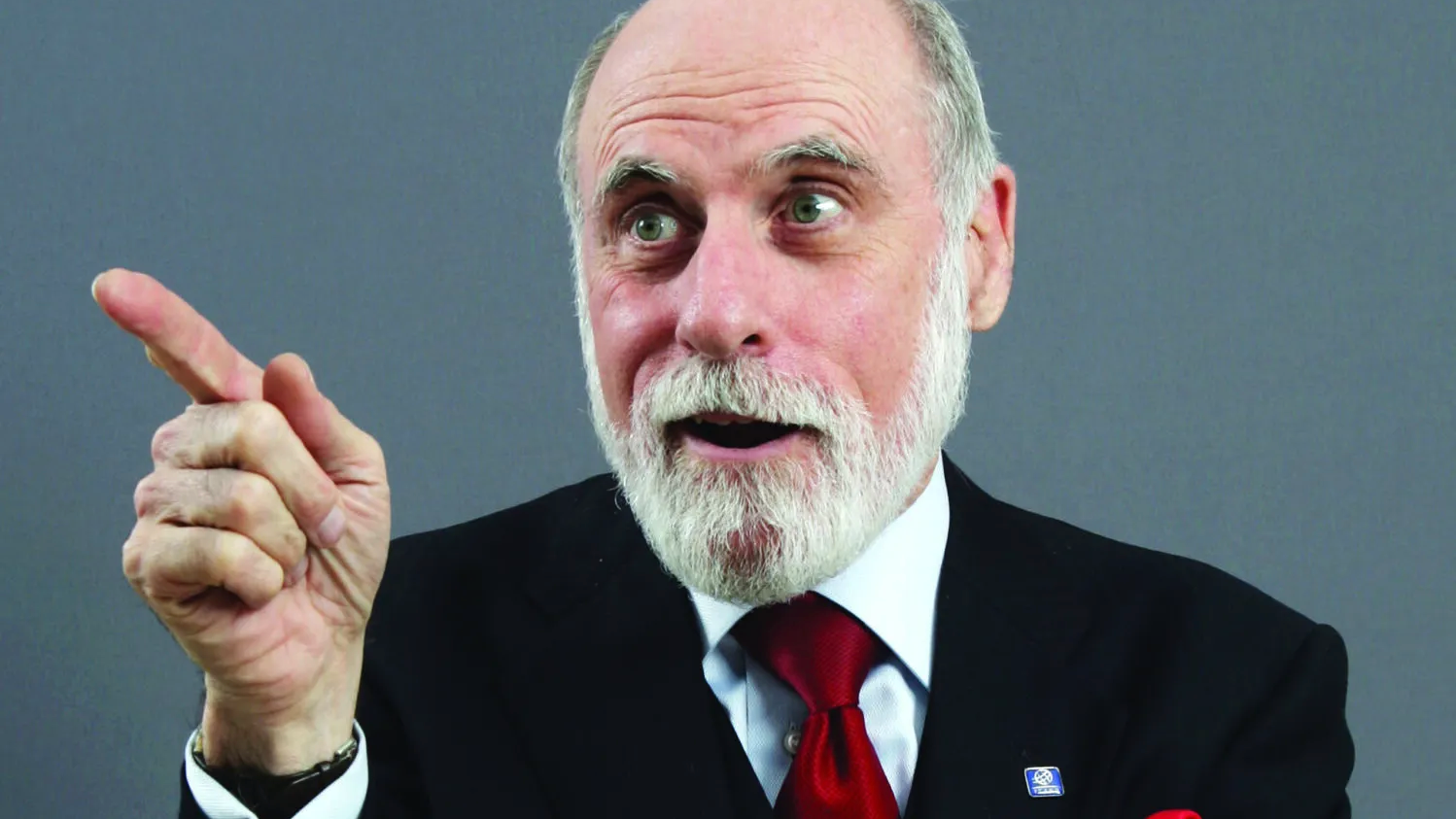

In the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI), few voices reflect as much experience in technology policy matters as that of Craig Mundie.

Although officially retired from his role as Senior Advisor to the CEO at Microsoft and former Chief Research and Strategy Officer, Mundie continues to advise the company, and played a role facilitating agreement with OpenAI. As such, he has access to the most advanced iterations of ChatGPT and other LLM-based platforms. Although there are risks inherent in AI development, Mundie thinks the enormous upside of AI is getting underplayed.

“The most significant power of these machines will be their polymathic ability to reason in high-dimensional spaces,” Mundie says. “Things that humans would never be able to do will be things these machines will do readily. Harnessing that, I think, is where the real gifts start being given.”

Join us at TE23 in Lake Nona, FL, as we dive into AI development’s opportunities, threats, and challenges. From healthcare to agriculture, government to climate, transportation to finance, our expert speakers will delve into how AI will revolutionize every industry. Request an invitation.

Understanding human biology, for example, is a task of staggering complexity beyond the ability of human understanding. A sufficiently trained AI, however, could be up for the task. AlphaFold’s ability to map the 3D structures of more than 200M proteins was a job only AI succeeded in doing despite decades of efforts by teams using more conventional approaches.

“Human biology is too complicated for humans, and I think it will always be.” Mundie says. “but it’s not going to be too complicated for these machines, and so the qualitative change comes when we can have a full model of human biology understood by these machines.”

When that occurs, the benefits will be multifold. On a basic level, AI can eliminate some of the drudgery of practicing medicine. On a higher level, AI’s ability to understand things in these high-dimensional spaces and be an effective communication machine will allow it to identify problems as a clinician would, but with greater range and, ultimately, greater accuracy.

“Using AI and some molecular biology, we test people early in their life, determine if they will have a particular condition, and tell them what they can do to prevent it from occurring,” Mundie says. “That will be a big breakthrough and represents a move toward prevention instead of just cure.”

As for the inevitability of government regulation, Mundie says the current debates fail to capture the complexity of the problem. The government and many AI companies say they want to build an oversight structure but now need to learn how to actually do it.

“It’s hard to think through regulations before you’ve built anything,” Mundie says. “That’s why I certainly applaud the decisions that Sam Altman and the OpenAI people made, which was to say, look, while this thing is powerful but not yet truly dangerous, we need to get a lot more real-world exposure and then use that to help guide the evolution of a longer-term strategy.”

Ultimately, we will need AIs to mitigate their own downside risks. AI-driven misinformation, cyberattacks, and fraud must be met with AI-driven defense systems. It is a tall order, but it begs an even bigger question for Mundie: How do our institutions adjust to a world where humans are no longer the smartest game in town?

The disruptions could be major. “The Westphalian model of nation-states that the world happily lives with today has only been around for a few hundred years,” Mundie says. “What happens down the road? Are the nation-states as we know them the thing we stay with, or do we go to something else? If we become a space-faring people or if interplanetary neighbors start showing up, what happens then? AIs are going to play some role in all of this.”

Techonomy 23: The Promise and Peril of AI

Techonomy 23: is a three-day retreat dedicated to exploring the risks and rewards of the AI revolution. Join our live audience of 200 CEOs, CTOs, policymakers, academics, and thought leaders as we chart a course...