One thing was clear at last night’s New York premiere of Decoding Annie Parker, a movie about a woman with breast cancer: the film is a labor of love made by people who believe the dramatized true story they tell is important. (Held at the Directors Guild Theater, the premiere was a benefit for the American Cancer Society.)

No major studios were involved, and though it has a top-shelf cast (including Helen Hunt, Bradley Whitford, Rashida Jones, and Aaron Paul), the actors agreed to work for a fraction of their usual fees. When Annie Parker opens in select theaters this summer, it will be because a group of writers, donors, and cancer advocates were committed to sharing the lessons of Annie’s story.

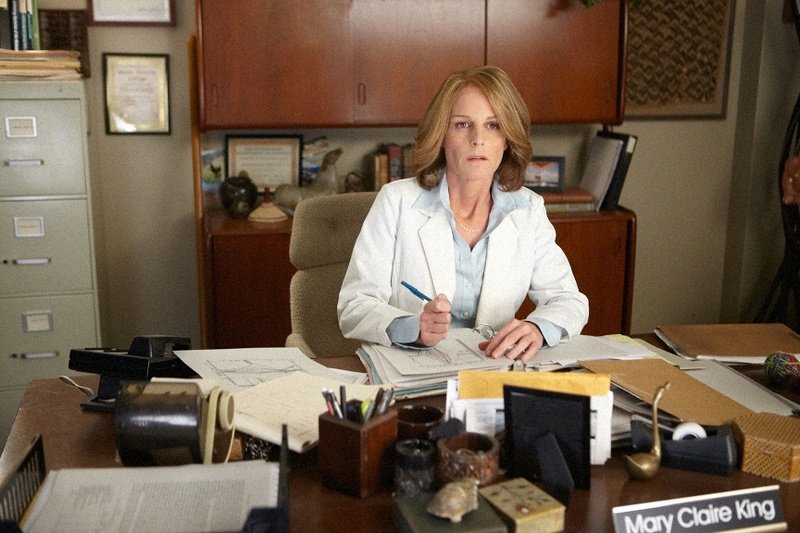

Which is, in a nutshell, this: After watching her mother and sister die of breast cancer in the ’60s and ’70s, Annie Parker (played by Samantha Morton) receives the same diagnosis in 1980 and eventually becomes one of the first women in the world to have her genes analyzed for breast cancer susceptibility (genes known as BRCA1 and BRCA2). The analysis confirmed it to be an inherited form of the disease. The movie weaves the story of Annie’s battle against cancer with that of Mary-Claire King (played by Helen Hunt), a pioneering genetic researcher hunting for the gene she alone believes is responsible for certain cases of breast cancer.

Proof that the BRCA gene existed was found by King’s lab in 1990, so in other hands this movie might be simply a recounting of two women facing great personal and professional obstacles. But director Steven Bernstein makes the tale relevant and inspiring. Throughout the film, Annie Parker is convinced that breast cancer runs in her family and that she must have been born with a predisposition to the disease, even though every doctor assures her this is impossible. In the parallel thread, Mary-Claire King struggles to conduct the research that would prove the disease can be inherited, failing again and again to secure funding because her hypothesis runs counter to conventional wisdom. Much of the tension in the film comes from the women’s passion putting them on the wrong side of the medical establishment. In Annie’s quest to educate herself and move from being a passive patient to an informed and active advocate for her own health, we see a theme that echoes today as people use new technology to take more control of their medical data and treatment.

The real Annie Parker, who attended the benefit screening, spoke afterward and said that while nobody else in her life understood her near-obsessive need to learn about cancer, “I felt I was caught up in the middle of this storm and I had to stay the course.” Ms. Parker has been diagnosed with cancer three times and has beaten it each time.

Another modern theme comes from the topic of gene patenting, which is mentioned in passing at the end of the movie but will certainly get plenty of attention as the Supreme Court case challenging the patentability of the BRCA genes begins on April 15.

People familiar with genetics will appreciate that the film faithfully, if briefly, depicts the science of the time. In one scene, Mary-Claire King tells a visitor that the human genome contains 100,000 genes—this was indeed the widely held view at the time, though that number has since been revised to about 20,000.

In comments after the screening, director Bernstein spoke about the challenge of making the film when traditional Hollywood funding sources were unavailable. The indie film was instead financed by a few champions and supported by cancer advocacy groups, including the American Cancer Society. There will be two more benefit screenings, one in Palm Beach, Fla., and the other in Dallas, before the movie heads to a small number of commercial theaters this summer, where it is likely to have significant impact on the debate over genomics, treatment, and cancer.

Cancer Genetics Goes Indie: Decoding Annie Parker Premieres

One thing was clear at last night’s New York premiere of Decoding Annie Parker, a movie about a woman with breast cancer: the film is a labor of love made by people who believe the dramatized true story they tell is important. No major studios were involved, and though it has a top-shelf cast (including Helen Hunt, Bradley Whitford, Rashida Jones, and Aaron Paul), the actors agreed to work for a fraction of their usual fees. When Annie Parker opens in select theaters this summer, it will be because a group of writers, donors, and cancer advocates were committed to sharing the lessons of Annie’s story.