The Oklahoma State University Cowboys weren’t supposed to win their October 2009 game against the Texas A&M Aggies. OSU was playing without their top receiver, who was sidelined for an NCAA rules violation. Cowboy Running back Kendall Hunter, the best rusher in the Big 12 in 2008, was on the bench with an injured ankle. Quarterback Zac Robinson’s grandfather had just died of cancer, a heavy loss for the young man. And OSU was playing in College Station, Texas, in front of tens of thousands of rabid A&M fans. But the offensively depleted Cowboys took the field and still managed to pound the Aggies’ defense. By the fourth quarter, they were up 29–25 and began a relentless 93-yard drive that consumed eight minutes for another touchdown. The Cowboys hung on to win, 36–31.

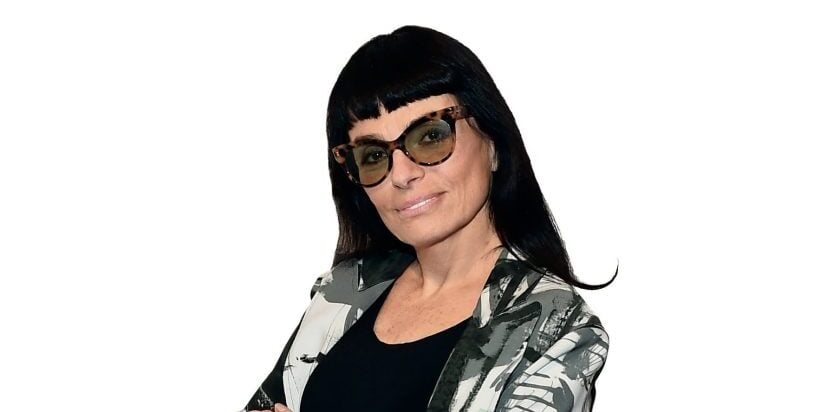

Their victory was in large part due to the almost invisible mastery of left tackle Russell Okung. The heart of the Aggies’ defense was linebacker Von Miller, later a Super Bowl MVP with the Denver Broncos, whose ability to sack quarterbacks had decimated prior opponents. The pregame consensus: Miller would spend most of the game harassing OSU quarterback Robinson. But that never happened. On play after play, the 6’5”, 310-pound Okung would surge out of his squat, arms swinging forward, to deflect the charging Miller away from Robinson. Miller didn’t get a single sack that day, and Okung, a senior, positioned himself as a top pick for that year’s NFL draft. The New York Times called Okung “perhaps the best left tackle in college football,” and the Seattle Seahawks picked him sixth in the draft and gave him a six-year, $48 million contract. That was a huge number for a rookie tackle, especially considering that $29 million of it was guaranteed.

For most athletes, a high draft pick and hefty contract would be the defining event of their career, topped only perhaps by a Super Bowl ring. But when Okung entered free agency six years later—years in which he proved himself to be one of the league’s standout offensive linemen, helping the Seahawks to win a Super Bowl in 2014—he made a highly unusual decision, closely watched within the small world of pro football players and the high-priced agents who represent them: He chose to do without an agent and represent himself in contract negotiations.

“My mother told me I was peculiar, I was different, and to act that way,” Okung told me. He decided to represent himsef because he’d grown tired of people “who weren’t representing me well or giving me the respect that I deserve.”

In the tightly controlled, conservative world of professional football, athletes don’t go their own way. Rejecting agents is virtually unheard-of and systemically discouraged. The collective bargaining agreement for the league actually prohibits players entering free agency from negotiating directly with teams until the free agency period has officially opened, which essentially puts them at a disadvantage relative to players who use agents. And agents, who take a 1.5 to 3 percent cut of every deal, promote the idea that self-representation means financial apocalypse. Okung recalls “getting hate text messages from agents” who he says planted negative stories in the press. “I don’t know how they got my number,” he says. “They’re hitting me up: ‘You’re not going to sign a good deal without one of us.’

“There’s a business model that has thrived off the player being the player and the representation being the representation,” Okung says. “I’m brushing up against a very traditional model that makes a ton of money. And if there’s anything that comes up against that system, there’s real resistance.”

In 2016, Okung signed a one-year contract with the Denver Broncos for $5 million, assuming that he fulfilled certain playing requirements; the Broncos also got the rights to sign him for another four years for an additional $48 million. Pundits quickly dubbed the contract a failure for its lack of guaranteed money. “The deal is rotten for player and perfect for team,” said SB Nation, a sports website owned by Vox Media. “It’s not likely we’ll see other players looking at it as a reason to jump into the ‘be your own agent’ pool anytime soon.” Columnist Mike Florio on the NBC Sports website ProFootballTalk said Okung needed to “hire a good and experienced agent,” and fast.

Okung was bullish on the Broncos deal. At the end of his first season, after successfully activating additional provisions in the contract, he had earned $8 million, saving himself some $200,000 in agent fees. Then, in March 2017, the Broncos declined to renew his contract, and it looked like the naysayers had been right after all. Okung had gambled that the Broncos would re-sign him, and they didn’t. But Okung, who was in Seattle the day the Broncos made the announcement, was unfazed. When asked if he was going to fly around the country meeting with teams, as he had done the first time around, he said no—the teams would come to him. There were more teams looking for left tackles at the beginning of 2017 than there were quality tackles on the market, and draft prospects were equally slim.

Okung was bullish on the Broncos deal. At the end of his first season, after successfully activating additional provisions in the contract, he had earned $8 million, saving himself some $200,000 in agent fees. Then, in March 2017, the Broncos declined to renew his contract, and it looked like the naysayers had been right after all. Okung had gambled that the Broncos would re-sign him, and they didn’t. But Okung, who was in Seattle the day the Broncos made the announcement, was unfazed. When asked if he was going to fly around the country meeting with teams, as he had done the first time around, he said no—the teams would come to him. There were more teams looking for left tackles at the beginning of 2017 than there were quality tackles on the market, and draft prospects were equally slim.

He was right. Within two weeks, the Los Angeles Chargers signed Okung to a four-year, $53 million contract, with $25 million guaranteed—more money than the Broncos would have paid him. “The economics of supply and demand really held true ” Okung says. “I strategically positioned myself in such a way that I’d be commanding dollars.”

Russell Okung was born on October 7, 1987, in Alief, a diverse neighborhood on the western edge of Houston. His parents, Dorothy Akpabio and Victor Okung, were Nigerian immigrants who met only after they arrived in Texas. Victor had a penchant for business and owned a gas station. “He was this great entrepreneur,” Okung says. His mother was one of 12 kids, all of whom were professionals—a doctor, a judge, a wealthy businessman. At an early age, Okung understood, “Our family is not made to be subservient in any way.”

On November 21, 1992, when Russell was 5, 14 tornados touched down in East Texas, beginning what became known as the “widespread outbreak,” three days of freak cyclone activity stretching across the southern U.S. High winds continued into November 22, but by the 23rd, a Monday, it seemed the world had finally calmed again, and Victor went to work at his gas station. Suddenly, several men appeared demanding money. One of them shot Victor twice, once in the chest and once in the back, killing him. “My father was shot in cold blood,” Okung says.

Okung clearly still grieves—although he remembers very little about his dad, his most prized possession is a Bible Victor gave him. But the murder also created “a determination not to have an end to my life like the one he had,” says Okung. “I’ve always wanted to be more than my circumstances and more than my environment.”

In the aftermath, Dorothy found herself an immigrant single mother of two, working day and night just to pay the bills. Education was very important in her household—Okung recalls being required to read eight books a month—and football became the financial key to a college education. Okung started playing flag football at age 8, but he wasn’t an immediate standout on the George Bush High School football team. “He was a good kid,” former coach Scott Moehlig told the Seattle Times in 2010. “His character is just unbelievable. But he was very quiet when he was a freshman, and I thought he liked basketball more.” But Okung grew taller and gained weight, and by his senior year football powerhouses like Oklahoma State, the University of Nebraska and Louisiana State were recruiting him. He chose OSU.

In Stillwater, where he studied marketing, Okung came into his own as a powerful, skillful offensive tackle. After the A&M game, Okung was voted All-Big 12 Offensive Lineman of the Year and a unanimous All-American pick. “I looked around to see what kind of leaders were already on the team and make sure I was connected to them, and Russell just stood out,” says Andrew McGee, who was a year behind Okung at Oklahoma.

But Okung’s college experience wasn’t perfect. Growing up in the South and then attending college in mostly white, deeply conservative Oklahoma, he faced racism in many forms. When he went shopping, he’d be followed by store security. At gas stations, he was “ostracized.”

“I remember for Halloween a fraternity dressed up as inmates and painted their faces black,” Okung says. “They think it’s a joke. They think it’s a game.”

It was clear to Okung that the world off the football field was more complicated than the one on it. You couldn’t count on the game for security—even of the financial kind. McGee would also be an NFL prospect, a top college cornerback who got a tryout with the Chicago Bears. But neck, back and wrist injuries scuttled his pro career before it began. In a different world, it could have been McGee joining the Seahawks and Okung facing injuries. “The average career in the NFL is two and a half years,” Okung says. “A lot of players are saying, ‘What do I do after? Do I want to go into business? Do I just want to invest all of my money and hang out for the next 30 years?’”

Seattle 2009 was the perfect place for an ambitious athlete who wanted to transcend the world of sports. Home to innovative companies such as Amazon, Microsoft, Starbucks and Boeing, the city is awash in technical expertise and venture capital. And its entrepreneurial culture has a reputation for being more welcoming to newcomers than that of, say, San Francisco. Plus, Seattle loves the Seahawks. But for someone whose world revolved around football since childhood, it’s hard to just jump into business. So, in the spring of 2013, Okung applied for an internship at Starbucks.

“He met with my boss at the time, Mary Kersbergen, and then he met with me independently,” says Tina Metcalf, executive assistant to Adam Brotman, Starbucks EVP for global retail operations and partner digital engagement. “He asked very good questions and followed up. He’s one of those people you can immediately connect with.” At the time, Metcalf was working on a team that handled Starbucks’ gift card, mobile app and digital operations. Working with her provided Okung with a broad introduction to the tech industry. “In hanging out with these people and seeing how they think through disruption and innovation, who can help but be inspired?” says Okung.

He quickly progressed from shadowing at Starbucks to sitting with Seattle-area venture capitalists and quizzing them about their investment portfolios, how they pick companies and what traits they look for in entrepreneurs. His status as a star for the Seahawks opened doors, and he found people eager to talk to him. One of Okung’s early mentors was Steve Hall, managing director of Microsoft cofounder and Seahawks owner Paul Allen’s venture capital firm, Vulcan Capital.

The two still meet regularly, and on a chilly afternoon in March I sat with them in Zeitgeist, a Seattle coffee shop, as they sipped lattes and talked about the challenges of investing in African startups. In between friendly banter about mutual friends, Okung asked pointed questions about the valuation of startups, how to evaluate their potential markets and what it took to reproduce tech concepts in different cultures.

Later that day, in a nearby coworking space, Okung joined T.A. McCann, another Seattle–area investor whom Okung had met through Hall. A former America’s Cup sailor, he helps vet investment ideas that people often bring to Okung. “Whenever you’re a celebrity, or perceived as one, people approach you with random, not very good startup ideas,” McCann says. “The least I can do to be helpful is say, ‘It’s not something I would be interested in.’”

McCann has advised Okung on several angel investments, and the two have co-invested together as well. He says that Okung’s athletic experience is crucial to his investing, though not in the way you might think. “It’s not the competitive mind-set.” Rather, it’s “dealing with a significant amount of risk. Doing startups is competitive, sure, but it’s also just a freaking grind. It’s so much persistence and trial and error and success and failure. If you’re a professional athlete, you get a lot of that.”

Okung has invested in seven tech companies involved in everything from the gasoline marketplace to e-sports. He prefers to invest in companies that combine the profit motive with a social mission: One of his favorite portfolio companies is Andela, which outsources software development to Lagos and Nairobi in an effort to build a tech industry in Africa similar to the one that now thrives in India. And as his business confidence has grown, Okung has begun to sound off on bigger issues.

In 2016, Paul Graham, cofounder of Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator and one of the most influential people in tech, penned an essay on economic inequality. In the piece, which was published on his blog, paulgraham.com, he argued that while he was “all for shutting down the crooked ways to get rich,” doing so wouldn’t “eliminate great variations in wealth.” The defining trait of people who become wealthy, Graham wrote, is a lack of laziness.

Okung responded in a passionate but measured essay on the techie website GeekWire. He began by asking the reader to imagine what would happen if the Seahawks were given pads to play with and the Vikings had to play without: “Two teams equal in athletic ability, no longer equal in access…. Some think working hard solves the problems of poverty, institutional oppression and the lack of social mobility. Some think that by sheer determination, one can overcome such issues. But economic inequality isn’t the symptom; it’s the virus that attacks.” Graham, Okung concluded, “may have lost his way.”

Nine months later, Okung wrote another essay, this time for the Players’ Tribune, in support of Colin Kaepernick’s protest during the national anthem. His theme was an expression of solidarity with the San Francisco quarterback and a tradition of black athletes using sports as a platform for protest. In the essay, Okung presented what was essentially his manifesto.

“As a society, we so often want to see the arenas and fields solely as a place for play. But what many people miss is the transcendent power of sport. Athletics has always been part of our political context and has played an important role in shaping the culture we are a part of. And that’s not just the case here in America; it’s been true around the globe…. Sports can create hope where once there was only despair. And, in some cases, athletics can be more powerful than government in breaking down racial barriers.”

Okung’s essay concluded by introducing his recently founded nonprofit, the Greater Foundation. Now two years old, Greater marries Okung’s twin passions of sports and technology by bringing underprivileged high school kids to the campuses of Seattle’s major tech companies for daylong hack-a-thons. The foundation’s March event, cosponsored by Amazon’s Black Employee Network, took place at Amazon’s trendy “Arizona” building. Around 60 high school students, predominantly African American, Latino and Pacific Islander, participated.

The kids split into teams, and each team was assigned a mentor, a black engineer from Amazon. For many of these students, this was not only their first time on a corporate campus but also their first time meeting minority engineers. “There are so many things happening in the technology sector, but traditionally, minorities haven’t been included in that,” says Andrew McGee, Okung’s old OSU teammate, who left a job coaching football at the West Virginia University to run Greater. “We think it’s an injustice if there’s no access or opportunities for everyone in this field.”

At the Amazon event, the kids worked with engineers to come up with ideas for apps to run on the company’s Alexa system and then devise business plans for those apps. Finally they presented their concept to a panel of judges, including Okung and hip-hop emcee Sway Calloway, in a Shark Tank–style setting. One team proposed an app that would help kids deal with emotional issues related to absent fathers. “What are the common factors that tie those kids together? Fatherlessness and low income,” Okung says.

For the teenagers, the experience shows them possibility. “It gets you out of your comfort zone, to communicate a business pitch,” 18-year-old Brando Sio tells me. “It’s good to know that if you have mentors like that, they’ll help you.” Another student, Alissa Hill-Gegrate, 16, says Okung “is like an older brother to everyone here.” A third student, James Lawrence, 15, calls the event “wonderful” because it gave him a chance to have “his voice heard” and to work with engineers at Amazon “and be in their shoes for a day.”

And it doesn’t stop with the hack-a-thons. Greater is negotiating with code schools in Seattle to offer scholarships and subsidized tuition for kids who have gone through their program, to ensure that what starts as an introduction to entrepreneurship at a hack-a-thon can actually be a career option.

Many of the participants in Greater’s programs attend the Seattle Urban Academy, a religious alternative high school that works with students who have dropped out of the regular school system and may be facing abuse at home, crime and homelessness.

“I feel like sports outpaces our society and our culture.”

“When I first came to SUA, all of them wanted to do the exact same thing I was doing,” Okung says. “What they see is a way to provide for their family. They know that the field and the court can bring meaningful change to their community and neighborhood and their family. And it’s hard to make that assessment about something else if you’ve never experienced it.”

He particularly tries to reach students on the high school football team—he and McGee attend their games regularly. At one away game at a rural school, racist taunts led to the eruption of a fight among the players. Okung wasn’t there that day, but back in Seattle, he gathered the team to talk about what happened. The kids, who were still reeling from the experience, were glad to have someone they trusted to share their feelings with. “Andrew’s from Mississippi, and I’m from Texas, and we have both in some ways been victims of prejudice and that system of oppression,” Okung says. “Our response isn’t to lash out or to give authenticity to what they do. When they go low, we go high.”

So far, Okung has invested around $750,000 in the Greater Foundation, and he’s constantly looking for ways to use his celebrity and connections in the tech world to improve lives in his community. “I feel like sports outpaces our society and our culture,” Okung says. “I’ve grown up with people from all socioeconomic backgrounds. In those instances, race doesn’t matter. If you look at history—whether you’re talking Jackie Robinson or some of the other great African American athletes—that’s why schools were integrated. You see these figures standing in the gap still.”

It’s a fundamentally political statement. When asked what he wanted to be as a child, Okung doesn’t say football player or even businessman. “I wanted to be president,” he says. Now, when asked if he would ever get into politics, at first he says he doesn’t know. Then, he shifts: “I’d consider it…Everyone on my team thinks I’m meant to be a politician.”

For more information, contact: Andrew McGee,[email protected], begreater.org.